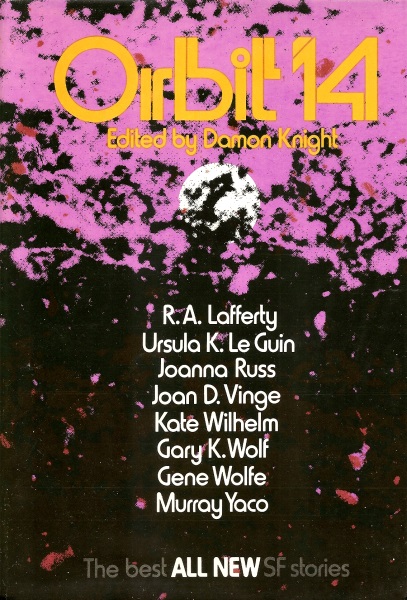

ORBIT 14

Edited by Damon Knight

HARPER & ROW, PUBLISHERS

New York, Evanston, San Francisco, London

Copyright © 1974 by Damon Knight. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, N.Y. 10022. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto.

FIRST EDITION

Designed by C. Linda Dingier

ISBN: 0-06-012438-5

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 73-18657

They Say

The lead story [in Astounding Stories, December 1933] was Nat Schachner’s “Ancestral Voices,” in which a time traveler, having returned to the past, happens to kill a ferocious Hun who, unknown to the traveler, is one of his own ancestors. This brings about the immediate nonexistence of the time traveler as well as that of many thousands of people throughout history. Above all, the Hun’s death causes the disappearance in 1933 of Hitler and numerous Nazis, along with an equally large number of Jews! Thus Schachner denounced the myth of the superiority of the “Aryan race” along with that of the “chosen people.” Jews or Nazis, all men are of the same race. This very courageous story, written at a time when Hitlerism had many supporters in the United States, caused a shock among the readers. Certain admirers of the Third Reich went so far as to threaten the editors with reprisals; adult science fiction was born.

—Jacques Sadoul, in Hier, I’An 2000 (Denoel, Paris, 1973)

“I owe what I am entirely to paperbacks. I am a PX and bus station author; and I’m lucky because people think of my books as science fiction, and they always print a lot of copies of science fiction.”

—Kurt Vonnegut, at the Bookworkers’ seminar on “Open Publishing,” New York, April 9, 1973 (reported in Publishers Weekly)

Here is the typical product of America, as seen by those who are repelled by America but who like the Americans. As an individual, he so perfectly represents that country, crammed with blinding faults and made up of often delightful people, that he seems a parody of it: the best conscience in the world, more extraverted than flesh and blood can be, a juvenile mentality furnished with an extravagant power (his talent), a purely visceral racism without any rational foundation, all this in the service of science fiction—it’s too much.

—Pierre Versins, Encyclopedic de I’Utopie et de la Science Fiction (L’Age d’Homme, Lausanne, 1972)

We who hobnob with hobbits and tell tall tales about little green men are quite used to being dismissed as mere entertainers, or sternly disapproved of as escapists. But I think that perhaps the categories are changing, like the times. Sophisticated readers are accepting the fact that an improbable and unmanageable world is going to produce an improbable and hypothetical art. At this point, realism is perhaps the least adequate means of understanding or portraying the incredible realities of our existence. A scientist who creates a monster in his laboratory; a librarian in the library of Babel; a wizard unable to cast a spell; a space ship having trouble in getting to Alpha Centauri: all these may be precise and profound metaphors of the human condition. The fantasist, whether he uses the ancient archetypes of myth and legend or the younger ones of science and technology, may be talking as seriously as any sociologist—and a good deal more directly—about human life as it is lived, and as it might be lived, and as it ought to be lived. For, after all, as great scientists have said and as all children know, it is above all by the imagination that we achieve perception, and compassion, and hope.

—Ursula K. Le Guin, accepting the National Book Award for Children’s Literature. New York, April 10, 1973

TIN SOLDIER

Joan D. Vinge

In Hans Christian Andersen’s immortal story, a tin soldier fell in love with a ballerina and passed through the fire for her. Their fate was cruel; but now, centuries later and light-years away, another tin soldier and his ballerina might have a second chance.

The ship drifted down the ragged light-robe of the Pleiades, dropped like a perfect pearl into the midnight water of the bay. And re-emerged, to bob gently in a chain of gleaming pearls stretched across the harbor toward the port. The port’s unsleeping Eye blinked once, the ship replied. New Piraeus, pooled among the hills, sent tributaries of light streaming down to the bay to welcome all comers, full of sound and brilliance and rash promise. The crew grinned, expectant, faces peering through the transparent hull; someone giggied nervously.

The sign at the heavy door flashed a red one-legged toy; tin soldier flashed blue below it. eat. drink, come back again. In green. And they always did, because they knew they could.

“Soldier, another round, please!” came over canned music.

The owner of the Tin Soldier, also known as Tin Soldier, glanced up from his polishing to nod and smile, reached down to set bottles out on the bar. He mixed the drinks himself. His face was ordinary, with eyes that were dark and patient, and his hair was coppery barbed wire bound with a knotted cloth. Under the curling copper, under the skin, the back of his skull was a plastic plate. The quick fingers of the hand on the goose-necked bottle were plastic, the smooth arm was prosthetic. Sometimes he imagined he heard clicking as it moved. More than half his body was artificial. He looked to be about twenty-five; he had looked the same fifty years ago.

He set the glasses on the tray and pushed, watching as it drifted across the room, and returned to his polishing. The agate surface of the bar showed cloudy permutations of color, grain-streak and whorl and chalcedony depths of mist. He had discovered it in the desert to the east—a shattered imitation tree, like a fellow traveler trapped in stasis through time. They shared the private joke with their clientele.

“—come see our living legend!”

He looked up, saw her coming in with the crew of the Who Got Her-709, realized he didn’t know her. She hung back as they crowded around, her short ashen hair like beaten metal in the blueglass lantern light. New, he thought. Maybe eighteen, with eyes of quicksilver very wide open. He smiled at her as he welcomed them, and the other women pulled her up to the agate bar. “Come on, little sister,” he heard Harkane say, “you’re one of us too.” She smiled back at him.

“I don’t know you . . . but your name should be Diana, like the silver Lady of the Moon.” His voice caught him by surprise.

Quicksilver shifted. “It’s not.”

Very new. And realizing what he’d almost done again, suddenly wanted it more than anything. Filled with bitter joy he said, “What is your name?”

Her face flickered, but then she met his eyes and said, smiling, “My name is Brandy.”

“Brandy . . .”

A knowing voice said, “Send us the usual, Soldier. Later, yes—?”

He nodded vaguely, groping for bottles under the counter ledge. Wood screeked over stone as she pulled a stool near and slipped onto it, watching him pour. “You’re very neat.” She picked nuts from a bowl.

"Long practice.”

She smiled, missing the joke.

He said, “Brandy’s a nice name. And I think somewhere I’ve heard it—”

“The whole thing is Branduin. My mother said it was very old.”

He was staring at her. He wondered if she could see one side of his face blushing. “What will you drink?”

“Oh ... do you have any—brandy? It’s a wine, I think; nobody’s ever had any. But because it’s my name, I always ask.”

He frowned. “I don’t . . . hell, I do! Stay there.”

He returned with the impossible bottle, carefully wiped away its gray coat of years and laid it gleaming on the bar. Glintings of maroon speared their eyes. “All these years, it must have been waiting. That’s where I heard it . . . genuine vintage brandy, from Home.”

“From Terra—really? Oh, thank you!” She touched the bottle, touched his hand. “I’m going to be lucky.”

Curving glasses blossomed with wine; he placed one in her palm. "Ad astra.” She lifted the glass.

"Ad astra; to the stars.” He raised his own, adding silently, Tonight . . .

They were alone. Her breath came hard as they climbed up the newly cobbled streets to his home, up from the lower city where the fluorescent lamps were snuffing out one by one.

He stopped against a low stone wall. “Do you want to catch your breath?” Behind him in the empty lot a weedy garden patch wavered with the popping street lamp.

“Thank you.” She leaned downhill against him, against the wall. “I got lazy on my training ride. There’s not much to do on a ship; you’re supposed to exercise, but—” Her shoulder twitched under the quilted blue-silver. He absorbed her warmth.

Her hand pressed his lightly on the wall. “What’s your name? You haven’t told me, you know.”

“Everyone calls me Soldier.”

“But that’s not your name.” Her eyes searched his own, smiling.

He ducked his head, his hand caught and tightened around hers. “Oh . . . no, it’s not. It’s Maris.” He looked up. “That’s an old name, too. It means ‘soldier,’ consecrated to the god of war. I never liked it much.”

“From ‘Mars’? Sol’s fourth planet, the god of war.” She bent back her head and peered up into the darkness. Fog hid the stars.

“Yes.”

“Were you a soldier?”

“Yes. Everyone was a soldier—every man—where I came from. War was a way of life.”

“An attempt to reconcile the blow to the masculine ego?”

He looked at her.

She frowned in concentration. “ ‘After it was determined that men were physically unsuited to spacing, and women came to a new position of dominance as they monopolized this' critical area, the Terran cultural foundation underwent severe strain. As a result, many new and not always satisfactory cultural systems are evolving in the galaxy. . . . One of these is what might be termed a backlash of exaggerated machismo—’ ”

“ ‘—and the rebirth of the warrior/chattel tradition.’ ”

“You’ve read that book too.” She looked crestfallen.

“I read a lot. New Ways for Old, by Ebert Ntaka?”

“Sorry ... I guess I got carried away. But, I just read it—”

“No.” He grinned. “And I agree with old Ntaka, too. Glatte— what a sour name—was an unhealthy planet. But that’s why I’m here, not there.”

“Ow—!” She jerked loose from his hand. “Ohh, oh . . . God, you’re strong!” She put her fingers in her mouth.

He fell over apologies; but she shook her head, and shook her hand. “No, it’s all right . . . really, it just surprised me. Bad memories?”

He nodded, mouth tight.

She touched his shoulder, raised her fingers to his lips. “Kiss it, and make it well?” Gently he caught her hand, kissed it; she pressed against him. “It’s very late. We should finish climbing the hill . . . ?”

“No.” Hating himself, he set her back against the wall.

“No? But I thought—”

“I know you did. Your first space, I asked your name, you wanted me to; tradition says you lay the guy. But I’m a cyborg, Brandy. . . . It’s always good for a laugh on the poor greenie, they’ve pulled it a hundred times.”

“A cyborg?” The flickering gray eyes raked his body.

“It doesn’t show with my clothes on.”

“Oh ...” Pale lashes were beating very hard across the eyes now. She took a breath, held it. “Do—you always let it get this far? I mean—”

“No. Hell, I don’t know why I ... I owe you another apology. Usually I never ask the name. If I slip, I tell them right away; nobody’s ever held to it. I don’t count.” He smiled weakly.

“Well, why? You mean you can’t—”

“I’m not- all plastic.” He frowned, numb fingers rapping stone. “God, I’m not. Sometimes I wish I was, but I’m not.”

“No one? They never want to?”

“Branduin”—he faced the questioning eyes—“you’d better go back down. Get some sleep. Tomorrow laugh it off, and pick up some flashy Tail in the bar and have a good time. Come see me again in twenty-five years, when you’re back from space, and tell me what you saw.” Hesitating, he brushed her cheek with his true hand; instinctively she bent her head to the caress. “Good-bye.” He started up the hill.

“Maris—”

He stopped, trembling.

“Thank you for the brandy . . .” She came up beside him and caught his belt. “You’ll probably have to tow me up the hill.”

He pulled her to him and began to kiss her, hands touching her body incredulously.

“It’s getting—very, very late. Let’s hurry.”

Maris woke, confused, to the sound of banging shutters. Raising his head he was struck by the colors of dawn, and the shadow of Brandy standing bright-edged at the window. He left the rumpled bed and crossed cold tiles to join her. “What are you doing?” He yawned.

“I wanted to watch the sun rise, I haven’t seen anything but night for months. Look, the fog’s lifting already: the sun burns it up, it’s on fire, over the mountains—”

He smoothed her hair, pale gold under a corona of light. “And embers in the canyon.”

She looked down across ends of gray mist slowly reddening; then back. “Good morning.” She began to laugh. “I’m glad you don’t have any neighbors down there!” They were both naked.

He grinned, “That’s what I like about the place,” and put his arms around her. She moved close in the circle of coolness and warmth.

They watched the sunrise from the bed.

In the evening she came into the bar with the crew of the Kiss And Tell-736. They waved to him, nodded to her and drifted into blue shadows; she perched smiling before him. It struck him suddenly that nine hours was a long time.

“That’s the crew of my training ship. They want some white wine, please, any kind, in a bottle.”

He reached under the bar. “And one brandy, on the house?” He sent the tray off.

“Hi, Maris . . .”

“Hi, Brandy.”

“To misty mornings.” They drank together.

“By the way”—she glanced at him slyly—“I passed it around that people have been missing something. You.”

“Thank you,” meaning it. “But I doubt if it’ll change any minds.”

“Why not?”

“You read Ntaka—xenophobia; to most people in most cultures cyborgs are unnatural, the next thing up from a corpse. You’d have to be a necrophile—”

She frowned.

“—or extraordinary. You’re the first extraordinary person I’ve met in a hundred years.”

The smile formed, faded. “Maris—you’re not exactly twenty-five, are you? How old are you?”

“More like a hundred and fifteen.” He waited for the reaction.

She stared. “But, you look like twenty-five? You’re real, don’t you age?”

“I age. About five years for every hundred.” He shrugged. “The prosthetics slow the body’s aging. Perhaps it’s because only half my body needs constant regeneration; or it may be an effect of the antirejection treatment. Nobody really understands it. It just happens sometimes.”

“Oh.” She looked embarrassed. “That’s what you meant by ‘come back and see me’ . . . and they meant—Will you really live a thousand years?”

“Probably not. Something vital will break down in another three or four centuries, I guess. Even plastic doesn’t last forever.”

“Oh . . .”

“Live longer and enjoy it less. Except for today. What did you do today? Get any sleep?”

“No—” She shook away disconcertion. “A bunch of us went out and gorged. We stay on wake-ups when we’re in port, so we don’t miss a minute; you don’t need to sleep. Really they’re for emergencies, but everybody does it.”

Quick laughter almost escaped him; he hoped she’d missed it. Serious, he said, “You want to be careful with those things. They can get to you.”

“Oh, they’re all right.” She twiddled her glass, annoyed and suddenly awkward again, confronted by the Old Man.

Hell, it can’t matter—He glanced toward the door.

“Brandy! There you are.” And the crew came in. “Soldier, you must come sit with us later; but right now we’re going to steal Brandy away from you.”

He looked up with Brandy to the brown face, brown eyes, and salt-white hair of Harkane, Best Friend of the Mactav on the Who Got Her-709. Time had woven deep nets of understanding around her eyes; she was one of his oldest customers. Even the shape of her words sounded strange to him now: “Ah, Soldier, you make me feel young, always . . . Come, little sister, and join your family; share her, Soldier.”

Brandy gulped brandy; her boots clattered as she dropped off the stool. “Thank you for the drink,” and for half a second the smile was real. “Guess I’ll be seeing you—Soldier.” And she was leaving, ungracefully, gratefully.

Soldier polished the agate bar, ignoring the disappointed face it showed him. And later watched her leave, with a smug, blank-eyed Tail in velvet knee pants.

Beyond the doorway yellow-green twilight seeped into the bay, the early crowds began to come together with the night. “H’lo, Maris . . . ?” Silver dulled to lead met him in a face gone hollow; thin hands trembled, clenched, trembled in the air.

“Brandy—”

“What’ve you got for an upset stomach?” She was expecting laughter.

“Got the shakes, huh?” He didn’t laugh.

She nodded. “You were right about the pills, Maris. They make me sick. I got tired, I kept taking them . . .” Her hands rattled on the counter.

“And that was pretty dumb, wasn’t it?” He poured her a glass of water, watched her trying to drink, pushed a button under the counter. “Listen, I just called you a ride—when it comes, I want you to go to my place and go to bed.”

“But—”

“I won’t be home for hours. Catch some sleep and then you’ll be all right, right? This is my door lock.” He printed large numbers on a napkin. “Don’t lose this.”

She nodded, drank, stuffed the napkin up her sleeve. Drank some more, spilling it. “My mouth is numb.” An abrupt chirp of laughter escaped; she put up a shaky hand. “I—won’t lose it.”

Deep gold leaped beyond the doorway, sunlight on metal. “Your ride’s here.”

“Thank you, Maris.” The smile was crooked but very fond. She tacked toward the doorway.

She was still there when he came home, snoring gently in the bedroom in a knot of unmade blankets. He went silently out of the room, afraid to touch her, and sank into a leather-slung chair. Filled with rare and uneasy peace he dozed, while the starlit mist of the Pleiades’ nebulosity passed across the darkened sky toward morning.

“Maris, why didn’t you wake me up? You didn’t have to sleep in a chair all night.” Brandy stood before him wrestling with a towel, eyes puffy with sleep and hair flopping in sodden plumb-bobs from the shower. Her feet made small puddles on the braided rug.

“I didn’t mind. I don’t need much sleep.”

“That’s what I told you.”

“But I meant it. I never sleep more than three hours. You needed the rest, anyway.”

“I know . . . damn—” She gave up and wrapped the towel around her head. “You’re a fine guy, Maris.”

“You’re not so bad yourself.”

She blushed. “Glad you approve. Ugh, your rug—I got it all wet.” She disappeared into the bedroom.

Maris stretched unwillingly, stared up into ceiling beams bronzed with early sunlight. He sighed faintly. “You want some breakfast?”

“Sure, I’m starving! Oh, wait—” A wet head reappeared. “Let me make you breakfast? Wait for me.”

He sat watching as the apparition in silver-blue flightsuit ransacked his cupboards. “You’re kind of low on raw materials.”

“I know.” He brushed crumbs off the table. “I eat instant breakfasts and frozen dinners; I hate to cook.”

She made a face.

“Yeah, it gets pretty old after half a century . . . they’ve only had them on Oro for half a century. They don’t get any better, either.”

She stuck something into the oven. “I’m sorry I was so stupid about it.”

“About what?”

“About ... a hundred years. I guess it scared me. I acted like a bitch.”

“No, you didn’t.”

“Yes, I did! I know I did.” She frowned.

“Okay, you did ... I forgive you. When do we eat?”

They ate, sitting side by side.

“Cooking seems like an odd spacer’s hobby.” Maris scraped his plate appreciatively. “When can you cook on a ship?”

“Never. It’s all prepared and processed. So we can’t overeat. That’s why we love to eat and drink when we’re in port. But I can’t cook now either—no place. So it’s not really a hobby, I guess, any more. I learned how from my father, he loved to cook . . .” She inhaled, eyes closed.

“Is your mother dead?”

“No—” She looked startled. “She just doesn’t like to cook.”

“She wouldn’t have liked Glatte, either.” He scratched his crooked nose.

“Calicho—that’s my home, it’s seven light years up the cube from this corner of the Quadrangle—it’s ... a pretty nice place. I guess Ntaka would call it ‘healthy,’ even . . . there’s lots of room, like space; that helps. Cold and not very rich, but they get along. My mother and father always shared their work . . . they have a farm.” She broke off more bread.

“What did they think about your becoming a spacer?”

“They never tried to stop me; but I don’t think they wanted me to. I guess when you’re so tied to the land it’s hard to imagine wanting to be so free. ... It made them sad to lose me—it made me sad to lose them; but, I had to go. . . .”

Her mouth began to quiver suddenly. “You know, I’ll never get to see them again, I’ll never have time, our trips take so long, they’ll grow old and die. . . .” Tears dripped onto her plate. “And I miss my h-home—” Words dissolved into sobs, she clung to him in terror.

He rubbed her back helplessly, wordlessly, left unequipped to deal with loneliness by a hundred years alone.

“M-Maris, can I come and see you always, will you always, always be here when I need you, and be my friend?”

“Always . . He rocked her gently. “Come when you want, stay as long as you want, cook dinner if you want, I’ll always be here. . . .”

* * * *

. . . Until the night, twenty-five years later, when they were suddenly clustered around him at the bar, hugging, badgering, laughing, the crew of the Who Got Her-709.

“Hi, Soldier!”

“Soldier, have we—”

“Look at this, Soldier—”

“What happened to—”

“Brandy?” he said stupidly. “Where’s Brandy?”

“Honestly, Soldier, you really never do forget a face, do you?”

“Ah-ha, I bet it’s not her face he remembers!”

“She was right with us.” Harkane peered easily over the heads around her. “Maybe she stopped off somewhere.”

“Maybe she’s caught a Tail already?” Nilgiri was impressed.

“She could if anybody could, the little rascal.” Wynmet rolled her eyes.

“Oh, just send us the usual, Soldier. She’ll be along eventually. Come sit with us when she does.” Harkane waved a rainbow-tipped hand. “Come, sisters, gossip is not tasteful before we’ve had a drink.”

“That little rascal.”

Soldier began to pour drinks with singleminded precision, until he noticed that he had the wrong bottle. Cursing, he drank them himself, one by one.

“Hi, Maris.”

He pushed the tray away.

“Hi, Maris.” Fingers appeared in front of his face; he started. “Hey.”

“Brandy!”

Patrons along the bar turned to stare, turned away again.

“Brandy—”

“Well, sure; weren’t you expecting me? Everybody else is already here.”

“I know. I thought-—I mean, they said . . . maybe you were out with somebody already,” trying to keep it light, “and—”

“Well, really, Maris, what do you take me for?” She was insulted. “I just wanted to wait till everybody else got settled, so I could have you to myself. Did you think I’d forget you? Unkind.” She hefted a bright mottled sack onto the bar. “Look, I brought you a present!” Pulling it open, she dumped heaping confusion onto the counter. “Books, tapes, buttons, all kinds of things to look at. You said you’d read out the library five times; so I collected everywhere, some of them should be new . . . Don’t you like them?”

“I . . .” he coughed, “I’m crazy about them! I’m—overwhelmed. Nobody ever brought me anything before. Thank you. Thanks very much. And welcome back to New Piraeus!”

“Glad to be back!” She stretched across the bar, hugged him, kissed his nose. She wore a new belt of metal inlaid with stones. “You’re just like I remembered.”

“You’re more beautiful.”

“Flatterer.” She beamed. Ashen hair fell to her breasts; angles had deepened on her face. The quicksilver eyes took all things in now without amazement. “I’m twenty-one today, you know.”

“No kidding? That calls for a celebration. Will you have brandy?”

“Do you still have some?” The eyes widened slightly. “Oh, yes! We should make it a tradition, as long as it lasts.”

He smiled contentedly. They drank to birthdays, and to stars.

“Not very crowded tonight, is it?” Brandy glanced into the room, tying small knots in her hair. “Not like last time.”

“It comes and it goes. I’ve always got some fisherfolk, they’re heavy on tradition. ... I gave up keeping track of ship schedules.”

“We don’t even believe our own; they never quite fit. We’re a month late here.”

“I know—happened to notice it. . . .” He closed a bent cover, laid the book flat. “So anyway, how did you like your first Quadrangle?”

“Beautiful—oh, Maris, if I start I’ll never finish, the City in the Clouds on Patris, the Freeport on Sanalareta . . . and the Pleiades . . . and the depths of night, ice and fire.” Her eyes burned through him toward infinity. “You can’t imagine—”

“So they tell me.”

She searched his face for bitterness, found none. He shook his head. “I’m a man and a cyborg; that’s two League rules against me that I can’t change—so why resent it? I enjoy the stories.” His mouth twitched up.

“Do you like poetry?”

“Sometimes.”

“Then—may I show you mine? I’m writing a cycle of poems about space, maybe someday I’ll have a book. I haven’t shown them to anybody else, but if you’d like—”

“I’d like it.”

“I’ll find them, then. Guess I should be joining the party, really, they’ll think I’m antisocial”—she winced—“and they’ll talk about me! It’s like a small town, we’re as bad as lubbers.”

He laughed. “Don’t—you’ll disillusion me. See you later. Uh . . . listen, do you want arrangements like before? For sleeping.”

“Use your place? Could I? I don’t want to put you out.”

“Hell, no. You’re welcome to it.”

“I’ll cook for you—”

“I bought some eggs.”

“It’s a deal! Enjoy your books.” She wove a path between the tables, nodding to sailor and spacer; he watched her laughing face merge and blur, caught occasional flashes of silver. Stuffing books into the sack, he set it against his shin behind the bar. And some time later, watched her go out with a Tail.

The morning of the thirteenth day he woke to find Brandy sleeping soundly in the pile of hairy cushions by the door. Curious, he glanced out into a water-gray field of fog. It was the first time she had come home before dawn. Home? Carefully he lifted her from the pillows; she sighed, arms found him, in her sleep she began to kiss his neck. He carried her to the bed and put her down softly, bent to . . . No. He turned away, left the room. He had slept with her only once. Twenty-five or three years ago, without words, she had told him they would not be lovers again. She kept the customs; a spacer never had the same man more than once.

In the kitchen he heated a frozen dinner, and ate alone.

“What’s that?” Brandy appeared beside him, mummified in a blanket. She dropped down on the cushions where he sat barefoot, drinking wine and ignoring the TD.

“Three-dimensional propaganda: the Oro Morning Mine Report. You’re up pretty early—it’s hardly noon.”

“I’m not sleepy.” She took a sip of his wine.

“Got in pretty early, too. Anything wrong?”

“No . . . just—nothing happening, you know. Ran out of parties, everybody’s pooped but me.” She cocked her head. “What is this, anyway ... an inquisition? ‘Home awfully early, aren’t you—?’ ” She glared at him and burst into laughter.

“You’re crazy.” He grinned.

“Whatever happened to your couch?” She prodded cushions.

“It fell apart. It’s been twenty-five years, you know.”

“Oh. That’s too bad . . . Maris, may I read you my poems?” Suddenly serious, she produced a small, battered notebook from the folds of her blanket.

“Sure.” He leaned back, watching subtle transformations occur in her face. And felt them begin to occur in himself, growing pride and a tender possessiveness.

. . . Until, lost in darkness, we

dance the silken star-song.

It was the final poem. “That’s ‘Genesis.’ It’s about the beginning of a flight . . . and a life.” Her eyes found the world again, found dark eyes quietly regarding her.

“ ‘Attired with stars we shall forever sit, triumphing over Death, and Chance, and thee, O Time.’ ” He glanced away, pulling the tassel of a cushion. “No . . . Milton, not Maris—I could never do that.” He looked back, in wonder. “They’re beautiful, you are beautiful. Make a book. Gifts are meant for giving, and you are gifted.”

Pleasure glowed in her cheeks. “You really think someone would want to read them?”

“Yes.” He nodded, searching for the words to tell her. “Nobody’s ever made me—see that way ... as though I ... go with you. Others would go, if they could. Home to the sky.”

She turned with him to the window; they were silent. After a time she moved closer, smiling. “Do you know what I’d like to do?”

“What?” He let out a long breath.

“See your home.” She set her notebook aside. “Let’s go for a walk in New Piraeus. I’ve never really seen it by day—the real part of it. I want to see its beauty up close, before it’s all gone. Can we go?”

He hesitated. “You sure you want to—?”

“Sure. Come on, lazy.” She gestured him up.

And he wondered again why she had come home early.

So on the last afternoon he took her out through the stone-paved winding streets, where small whitewashed houses pressed for footholds. They climbed narrow steps, panting, tasted the sea wind, bought fruit from a leathery smiling woman with a basket.

“Mmm—” Brandy licked juice from the crimson pith. “Who was that woman? She called you ‘Sojer,’ but I couldn’t understand the rest ... I couldn’t even understand you! Is the dialect that slurred?”

He wiped his chin. “It’s getting worse all the time, with all the newcomers. But you get used to everything in the lower city. . . . An old acquaintance, I met her during the epidemic, she was sick.”

“Epidemic? What epidemic?”

“Oro Mines was importing workers—they started before your last visit, because of the bigger raw material demands. One of the new workers had some disease we didn’t; it killed about a third of New Piraeus.”

“Oh, my God—”

“That was about fifteen years ago . . . Oro’s labs synthesized a vaccine, eventually, and they repopulated the city. But they still don’t know what the disease was.”

“It’s like a trap, to live on a single world.”

“Most of us have to ... it has its compensations.”

She finished her fruit, and changed the subject. “You helped take care of them, during the epidemic?”

He nodded. “I seemed to be immune, so—”

She patted his arm. “You are very good.”

He laughed; glanced away. “Very plastic would be more like it.”

“Don’t you ever get sick?”

“Almost never. I can’t even get very drunk. Someday I’ll probably wake up entirely plastic.”

“You’d still be very good.” They began to walk again. “What did she say?”

“She said, ‘Ah, Soldier, you’ve got a lady friend.’ She seemed pleased.”

“What did you say?”

“I said, ‘That’s right.’ ” Smiling, he didn’t put his arm around her; his fingers kneaded emptiness.

“Well, I’m glad she was pleased ... I don’t think most people have been.”

“Don’t look at them. Look out there.” He showed her the sea, muted greens and blues below the ivory jumble of the flat-roofed town. To the north and south mountains like rumpled cloth reached down to the shore.

“Oh, the sea—I’ve always loved the sea; at home we were surrounded by it, on an island. Space is like the sea, boundless, constant, constantly changing . . .”

“—spacer!” Two giggling girls made a wide circle past them in the street, dark skirts brushing their calves.

Brandy blushed, frowned, sought the sea again. “I—think I’m getting tired. I guess I’ve seen enough.”

“Not much on up there but the new, anyway.” He took her hand and they started back down. “It’s just that we’re a rarity up this far.” A heavy man in a heavy caftan pushed past them; in his cold eyes Maris saw an alien wanton and her overaged Tail.

“They either leer, or they censure.” He felt her nails mark his flesh. “What’s their problem?”

“Jealousy . . . mortality. You threaten them, you spacers. Don’t you ever think about it? Free and beautiful immortals—”

“They know we aren’t immortal; we hardly live longer than anybody else.”

“They also know you come here from a voyage of twenty-five years looking hardly older than when you left. Maybe they don’t recognize you, but they know. And they’re twenty-five years older. . . . Why do you think they go around in sacks?”

“To look ugly. They must be dreadfully repressed.” She tossed her head sullenly.

“They are; but that’s not why. It’s because they want to hide the changes. And in their way to mimic you, who always look the same. They’ve done it since I can remember; you’re all they have to envy.”

She sighed. “I’ve heard on Elder they paint patterns on their skin, to hide the change. Ntaka called them ‘youth-fixing,’ didn’t he?” Anger faded, her eyes grew cool like the sea, gray-green. “Yes, I think about it . . . especially when we’re laughing at the lubbers, and their narrow lives. And all the poor panting awestruck Tails, sometimes they think they’re using us, but we’re always using them. . . . Sometimes I think we’re very cruel.”

“Very like a god—Silver Lady of the Moon.”

“You haven’t called me that since—that night ... all night.” Her hand tightened painfully; he said nothing. “I guess they envy a cyborg for the same things. . . .”

“At least it’s easier to rationalize—and harder to imitate.” He shrugged. “We leave each other alone, for the most part.”

“And so we must wait for each other, we immortals. It’s still a beautiful town; I don’t care what they think.”

He sat, fingers catching in the twisted metal of his thick bracelet, listening to her voice weave patterns through the hiss of running water. Washing away the dirty looks—Absently he reread the third paragraph on the page for the eighth time; and the singing stopped.

“Maris, do you have any—”

He looked up at her thin, shining body, naked in the doorway. “Brandy, God damn it! You’re not between planets—you want to show it all to the whole damn street?”

“But I always—” Made awkward by sudden awareness, she fled.

He sat and stared at the sun-hazed windows, entirely aware that there was no one to see in. Slowly the fire died, his breathing eased.

She returned shyly, closing herself into quilted blue-silver, and sank onto the edge of a chair. “I just never think about it.” Her voice was very small.

“It’s all right.” Ashamed, he looked past her. “Sorry I yelled at you . . . What did you want to ask me?”

“It doesn’t matter.” She pulled violently at her snarled hair. “Ow! Damn it!” Feeling him look at her, she forced a smile. “Uh, you know, I’m glad we picked up Mima on Treone; I’m not the little sister anymore. I was really getting pretty tired of being the greenie for so long. She’s—”

“Brandy—”

“Hm?”

“Why don’t they allow cyborgs on crews?”

Surprise caught her. “It’s a regulation.”

He shook his head. “Don’t tell me ‘It’s a regulation,’ tell me why.”

“Well . . .” She smoothed wet hair-strands with her fingers. “. . . They tried it, and it didn’t work out. Like with men—they couldn’t endure space, they broke down, their hormonal balance was wrong. With cyborgs, stresses between the real and the artificial in the body were too severe, they broke down too. ... At the beginning they tried cyborganics, as a way to let men keep space, like they tried altering the hormone balance. Neither worked. Physically or psychologically, there was too much strain. So finally they just made it a regulation, no men on space crews.”

“But that was over a thousand years ago—cyborganics has improved. I’m healthier and live longer than any normal person. And stronger—” He leaned forward, tight with agitation.

“And slower. We don’t need strength, we have artificial means. And anyway, a man would still have to face more stress, it would be dangerous.”

“Are there any female cyborgs on crews?”

“No.”

“Have they ever even tried it again?”

' “No—”

“You see? The League has a lock on space, they keep it with archaic laws. They don’t want anyone else out there!” Sudden resentment shook his voice.

“Maybe ... we don’t.” Her fingers closed, opened, closed over the soft heavy arms of the chair; her eyes were the color of twisting smoke. “Do you really blame us? Spacing is our life, it’s our strength. We have to close the others out, everything changes and changes around us, there’s no continuity—we only have each other. That’s why we have our regulations, that’s why we dress alike, look alike, act alike; there’s nothing else we can do, and stay sane. We have to live apart, always.” She pulled her hair forward, tying nervous knots. “And—that’s why we never take the same lover twice, too. We have needs we have to satisfy; but we can’t afford to . . . form relationships, get involved, tied. It’s a danger, it’s an instability. . . . You do understand that, don’t you, Maris; that it’s why I don’t—” She broke off, eyes burning him with sorrow and, below it, fear.

He managed a smile. “Have you heard me complain?” “Weren’t you just . . . ?” She lifted her head.

Slowly he nodded, felt pain start. “I suppose I was.” But I don’t change. He shut his eyes suddenly, before she read them. But that’s not the point, is it?

“Maris, do you want me to stop staying here?”

“No— No ... I understand, it’s all right. I like the company.” He stretched, shook his head. “Only, wear a towel, all right? I’m only human.”

“I promise . . . that I will keep my eyes open, in the future.” He considered the future that would begin with dawn when her ship went up, and said nothing.

* * * *

He stumbled cursing from the bedroom to the door, to find her waiting there, radiant and wholly unexpected. “Surprise!” She laughed and hugged him, dislodging his half-tied robe.

“My God—hey!” He dragged her inside and slammed the door. “You want to get me arrested for indecent exposure?” He turned his back, making adjustments, while she stood and giggled behind him.

He faced her again, fogged with sleep, struggling to believe. “You’re early—almost two weeks?”

“I know. I couldn’t wait till tonight to surprise you. And I did, didn’t I?” She rolled her eyes. “I heard you coming to the door!”

She sat curled on his aging striped couch, squinting out the window as he fastened his sandals. “You used to have so much room. Houses haven’t filled up your canyon, have they?” Her voice grew wistful.

“Not yet. If they ever do, I won’t stay to see it . . . How was your trip this time?”

“Beautiful, again ... I can’t imagine it ever being anything else. You could see it all a hundred times over, and never see it all—

Through your crystal eye,

Mactav, I watch the midnight’s

star turn inside out. . . .

Oh, guess what! My poems—I finished the cycle during the voyage . . . and it’s going to be published, on Treone. They said very nice things about it.”

He nodded smugly. “They have good taste. They must have changed, too.”

“ ‘A renaissance in progress’—meaning they’ve put on some ver-ry artsy airs, last decade; their Tails are really something else. . . .” Remembering, she shook her head. “It was one of them that told me about the publisher.”

“You showed him your poems?” Trying not to—

“Good grief, no; he was telling me about his. So I thought, What have I got to lose?”

“When do I get a copy?”

“I don’t know.” Disappointment pulled at her mouth. “Maybe I’ll never even get one; after twenty-five years they’ll be out of print. ‘Art is long, and Time is fleeting’ . . . Longfellow had it backwards. But I made you some copies of the poems. And brought you some more books, too. There’s one you should read, it replaced Ntaka years ago on the Inside. I thought it was inferior; but who are we . . . What are you laughing about?”

“What happened to that freckle-faced kid in pigtails?”

“What?” Her nose wrinkled.

“How old are you now?”

“Twenty-four. Oh—” She looked pleased.

“Madame Poet, do you want to go to dinner with me?”

“Oh, food, oh yes!” She bounced, caught him grinning, froze. “I would love to. Can we go to Good Eats?”

“It closed right after you left.”

“Oh . . . the music was wild. Well, how about that seafood place, with the fish name—?”

He shook his head. “The owner died. It’s been twenty-five years.”

“Damn, we can never keep anything.” She sighed. “Why don’t I just make us a dinner—I’m still here. And I’d like that.”

That night, and every other night, he stood at the bar and watched her go out, with a Tail or a laughing knot of partyers. Once she waved to him; the stem of a shatterproof glass snapped in his hand; he kicked it under the counter, confused and angry.

But three nights in the two weeks she came home early. This time, pointedly, he asked her no questions. Gratefully, she told him no lies, sleeping on his couch and sharing the afternoon . . .

They returned to the flyer, moving in step along the cool jade sand of the beach. Maris looked toward the sea’s edge, where frothy fingers reached, withdrew, and reached again. “You leave tomorrow, huh?”

Brandy nodded. “Uh-huh.”

He sighed.

“Maris, if—”

“What?”

“Oh—nothing.” She brushed sand from her boot.

He watched the sea reach, and withdraw, and reach—

“Have you ever wanted to see a ship? Inside, I mean.” She pulled open the flyer door, her body strangely intent.

He followed her. “Yes.”

“Would you like to see mine—the Who Got Her?”

“I thought that was illegal?”

“ ‘No waking man shall set foot on a ship of the spaceways.’ It is a League regulation . . . but it’s based on a superstition that’s at least a thousand years old—‘Men on ships is bad luck.’ Which is silly here. Your presence on board in port isn’t going to bring us disaster.”

He looked incredulous.

“I’d like you to see our life, Maris, like I see yours. There’s nothing wrong with that. And besides”—she shrugged—“no one will know; because nobody’s there right now.”

He faced a wicked grin, and did his best to match it. “I will if you will.”

They got in, the flyer drifted silently up from the cove. New Piraeus rose to meet them beyond the ridge; the late sun struck gold from hidden windows.

“I wish it wouldn’t change—oh . . . there’s another new one. It’s a skyscraper!”

He glanced across the bay. “Just finished; maybe New Piraeus is growing up—thanks to Oro Mines. It hardly changed over a century; after all those years, it’s a little scary.”

“Even after three ... or twenty-five?” She pointed. “Right down there, Maris—there’s our airlock.”

The flyer settled on the water below the looming, semitransparent hull of the WGH-709.

Maris gazed up and back. “It’s a lot bigger than I ever realized.”

“It masses twenty thousand tons, empty.” Brandy caught hold of the hanging ladder. “I guess we’ll have to go up this . . . okay?” She looked over at him.

“Sure. Slow, maybe, but sure.”

They slipped in through the lock, moved soft-footed down hallways past dim cavernous storerooms.

“Is the whole ship transparent?” He touched a wall, plastic met plastic. “How do you get any privacy?”

“Why are you whispering?”

“I’m no— I’m not. Why are you?”

“Shhh! Because it’s so quiet.” She stopped, pride beginning to show on her face. “The whole ship can be almost transparent, like now; but usually it’s not. All the walls and the hull are polarized; you can opaque them. These are just holds, anyway, they’re most of the ship. The passenger stasis cubicles are up there. Here’s the lift, we’ll go up to the control room.”

“Brandy!” A girl in red with a clipboard turned on them, outraged, as they stepped from the lift. “Brandy, what the hell do you mean by— Oh. Is that you, Soldier? God, I thought she’d brought a man on board.”

Maris flinched. “Hi, Nilgiri.”

Brandy was very pale beside him. “We just came out to—uh, look in on Mactav, she’s been kind of moody lately, you know. I thought we could read to her. . . . What are you doing here?” And a whispered, “Bitch.”

“Just that—checking up on Mactav. Harkane sent me out.” Nilgiri glanced at the panels behind her, back at Maris, suddenly awkward. “Uh—look, since I’m already here don’t worry about it, okay? I’ll go down and play some music for her. Why don’t you— uh, show Soldier around the ship, or something . . Her round face was reddening Jike an apple. “Bye?” She slipped past them and into the lift, and disappeared.

“Damn, sometimes she’s such an ass.”

“She didn’t mean it.”

“Oh, I should have—”

“—done just what you did; she was sorry. And at least we’re not trespassing.”

“God, Maris, how do you stand it? They must do it to you all the time. Don’t you resent it?”

“Hell, yes, I resent it. Who wouldn’t? I just got tired of getting mad. . . . And besides—” he glanced at the closed doors—“besides, nobody needs a mean bartender. Come on, show me around the ship.”

Her knotted fingers uncurled, took his hand. “This way, please; straight ahead of you is our control room.” She pulled him forward beneath the daybright dome. He saw a hand-printed sign above the center panel, NO-MAN’S LAND. “From here we program our computer; this area here is for the AAFAL drive, first devised by Ursula, an early spacer who—”

“What’s awful about it?”

“What?”

“Every spacer I know calls the ship’s drive ‘awful’?”

“Oh— Not ‘awful,’ AAFAL: Almost As Fast As Light. Which it is. That’s what we call it; there’s a technical name too.”

“Um.” He looked vaguely disappointed. “Guess I’m used to—” Curiosity changed his face, as he watched her smiling with delight. “I—suppose it’s different from antigravity?” Seventy years before she was born, he had taught himself the principles of starship technology.

“Very.” She giggled suddenly. “The ‘awfuls’ and the ‘aghs,’ hmm, . . . We do use an ag unit to leave and enter solar systems; it operates like the ones in flyers, it throws us away from the planet, and finally the entire system, until we reach AAFAL ignition speeds. With the AG you can only get fractions of the speed of light, but it’s enough to concentrate interstellar gases and dust. Our force nets feed them through the drive unit, where they’re converted to energy, which increases our speed, which makes the unit more efficient . . . until we’re moving almost as fast as light.

“We use the AG to protect us from acceleration forces, and after deceleration to guide us into port. The start and finish can take up most of our trip time; the farther out in space you are, the less AG feedback you get from the system’s mass, and the less your velocity changes. It’s a beautiful time, though—you can see the AG forces through the polarized hull, wrapping you in shifting rainbow . . .

“And you are isolate”—she leaned against a silent panel and punched buttons; the room began to grow dark—“in absolute night . . . and stars.” And stars appeared, in the darkness of a planetarium show; fire-gnats lighting her face and shoulders and his own. “How do you like our stars?”

“Are we in here?”

Four streaks of blue joined lights in the air. “Here ... in space by this corner of the Quadrangle. This is our navigation chart for the Quadrangle run; see the bowed leg and brightness, that’s the Pleiades. Patris . . . Sanalareta . . . Treone . . . back to Oro. The other lines zigzag too, but it doesn’t show. Now come with me . . . With a flare of energy, we open our AAFAL nets in space—”

He followed her voice into the night, where flickering tracery seined motes of interstellar gas; and impossible nothingness burned with infinite energy, potential transformed and transforming. With the wisdom of a thousand years a ship of the League fell through limitless seas, navigating the shifting currents of the void, beating into the sterile winds of space. Stars glittered like snow on the curving hull, spitting icy daggers of light that moved imperceptibly into spectral blues before him, reddened as he looked behind: imperceptibly time expanded, velocity increased and with it power. He saw the haze of silver on his right rise into their path, a wall of liquid shadow . . . the Pleiades, an endless bank of burning fog, kindled from within by shrouded islands of fire. Tendrils of shimmering mists curved outward across hundreds of billions of kilometers, the nets found bountiful harvest, drew close, hurled the ship into the edge of cloud.

Nebulosity wrapped him in clinging haloes of- colored light, ringed him in brilliance, as the nets fell inward toward the ship, burgeoning with energy, shielding its fragile nucleus from the soundless fury of its passage. Acceleration increased by hundredfolds, around him the Doppler shifts deepened toward cerulean and crimson; slowly the clinging brightness wove into parabolas of shining smoke, whipping past until the entire flaming mass of cloud and stars seemed to sweep ahead, shriveling toward blue-whiteness, trailing embers.

And suddenly the ship burst once more into a void, a universe warped into a rubber bowl of brilliance stretching past him, drawing away and away before him toward a gleaming point in darkness. The shrunken nets seined near-vacuum and were filled; their speed approached 0.999c . . . held constant, as the conversion of matter to energy ceased within the ship . . . and in time, with a flicker of silver force, began once more to fall away. Slowly time unbowed, the universe cast off its alienness. One star grew steadily before them: the sun of Patris.

A sun rose in ruddy splendor above the City in the Clouds on Patris, nine months and seven light-years from Oro. . . . And again, Patris fell away; and the brash gleaming Freeport of Sana-lareta; they crept toward Treone through gasless waste, groping for current and mote across the barren ship-wakes of half a millennium. . . . And again—

Maris found himself among fire-gnat stars, on a ship in the bay of New Piraeus. And realized she had stopped speaking. His hand rubbed the copper snarl of his hair, his eyes bright as a child’s. “You didn’t tell me you were a witch in your spare time.”

He heard her smile, “Thank you. Mactav makes the real magic, though; her special effects are fantastic. She can show you the whole inhabited section of the galaxy, with all the trade polyhedra, like a dew-flecked cobweb hanging in the air.” Daylight returned to the panel. “Mactav—that’s her bank, there—handles most of the navigation, life support, all that, too. Sometimes it seems like we’re almost along for the ride! But of course we’re along for Mactav.”

“Who or what is Mactav?” Maris peered into a darkened screen, saw something amber glimmer in its depths, drew back.

“You’ve never met her, neither have we—but you were staring her right in the eye.” Brandy stood beside him. “She must be listening to Giri down below. . . . Okay, okay!—a Mactavia unit is the brain, the nervous system of a ship, she monitors its vital signs, calculates, adjusts. We only have to ask—sometimes we don’t even have to do that. The memory is a real spacer woman’s, fed into the circuits . . . someone who died irrevocably, or had reached retirement, but wanted to stay on. A human system is wiser, more versatile—and lots cheaper—than anything all-machine that’s ever been done.”

“Then your Mactav is a kind of cyborg.”

She smiled. “Well, I guess so; in a way—”

“But the Spacing League’s regulations still won’t allow cyborgs in crews.”

She looked annoyed.

He shrugged. “Sorry. Dumb thing to say . . . What’s that red down there?”

“Oh, that’s our ‘stomach’: the AAFAL unit, where”—she grinned —“we digest stardust into energy. It’s the only thing that’s never transparent, the red is the shield.”

“How does it work?”

“I don’t really know. I can make it go, but I don’t understand why—I’m only a five-and-a-half technician now. If I was a six I could tell you.” She glanced at him sidelong. “Aha! I finally impressed you!”

He laughed. “Not so dumb as you look.” He had qualified as a six half a century before, out of boredom.

“You’d better be kidding!”

“I am.” He followed her back across the palely opalescing floor, looking down, and down. “Like walking on water . . . why transparent?”

She smiled through him at the sky. “Because it’s so beautiful outside.”

They dropped down through floors, to come out in a new hall. Music came faintly to him.

“This is where my cabin—”

Abruptly the music became an impossible agony of sound torn with screaming.

“God!” And Brandy was gone from beside him, down the hallway and through a flickering wall.

He found her inside the door, rigid with awe. Across the room the wall vomited blinding waves of color, above a screeching growth of crystal organ pipes. Nilgiri crouched on the floor, hands pressed against her stomach, shrieking hysterically. “Stop it, Mactav! Stop it! Stop it! Stop it!”

He touched Brandy’s shoulder, she looked up and caught his arm; together they pulled Nilgiri, wailing, back from bedlam to the door.

“Nilgiri! Nilgiri, what happened!” Brandy screamed against her ear.

“Mactav, Mactav!”

“Why?”

“She put a . . . charge through it, she’s crazy-mad . . . sh-she thinks . . . Oh, stop it, Mactav!” Nilgiri clung, sobbing.

Maris started into the room, hands over his ears. “How do you turn it off!”

“Maris, wait!”

“How, Brandy?”

“It’s electrified, don’t touch it!”

“How?”

“On the left, on the left, three switches—Maris, don’t— Stop it, Mactav, stop—”

He heard her screaming as he lowered his left hand, hesitated, battered with glaring sound; sparks crackled as he flicked switches on the organ panel, once, twice, again.

“—it-it-it-it!” Her voice echoed through silent halls. Nilgiri slid down the doorjamb and sat sobbing on the floor.

“Maris, are you all right?”

He heard her dimly through cotton. Dazed with relief, he backed away from the gleaming console, nodding, and started across the room.

“Man,” the soft hollow voice echoed echoed echoed. “What are you doing in here?”

“Mactav?” Brandy was gazing uneasily to his left.

He turned; across the room was another artificial eye, burning amber.

“Branduin, you brought him onto the ship; how could you do this thing, it is forbidden!”

“Oh, God.” Nilgiri began to wail again in horror. Brandy knelt and caught Nilgiri’s blistered hands; he saw anger harden over her face. “Mactav, how could you!”

“Brandy.” He shook his head; took a breath, frightened. “Mactav—I’m not a man. You’re mistaken.”

“Maris, no . . .”

He frowned. “I’m one hundred and forty-one years old . . . half my body is synthetic. I’m hardly human, any more than you are. Scan and see.” He held up his hands.

“The part of you that matters is still a man.”

A smile caught at his mouth. “Thanks.”

“Men are evil, men destroyed . . .”

“Her, Maris,” Brandy whispered. “They destroyed her.”

The smile wavered. “Something more we have in common.” His false arm pressed his side.

The golden eye regarded him. “Cyborg.”

He sighed, went to the door. Brandy stood to meet him, Nilgiri huddled silently at her feet, staring up.

“Nilgiri.” The voice was full of pain; they looked back. “How can I forgive myself for what I’ve done? I will never, never do such a thing again . . . never. Please, go to the infirmary; let me help you?”

Slowly, with Brandy’s help, Nilgiri got to her feet. “All right. It’s all right, Mactav. I’ll go on down now.”

“Giri, do you want us—?”

Nilgiri shook her head, hands curled in front of her. “No, Brandy, it’s okay. She’s all right now. Me too—I think.” Her smile quivered. “Ouch . . .” She started down the corridor toward the lift.

“Branduin, Maris, I apologize also to you. I’m—not usually like this, you know. . . .” Amber faded from her eye.

“Is she gone?”

Brandy nodded.

“That’s the first bigoted computer I ever met.”

And she remembered: “Your hand?”

Smiling, he held it out to her. “No harm; see? It’s a nonconductor.”

She shivered. Hands cradled the hand that ached to feel. “Mactav really isn’t like that, you know. But something’s been wrong lately, she gets into moods; we’ll have to have her looked at when we get to Sanalareta.”

“Isn’t it dangerous?”

“I don’t think so—not really. It’s just that she has special problems; she’s in there because she didn’t have any choice, a strifebased culture killed her ship. She was very young, but that was all that was left of her.”

“A high technology.” A grimace; memory moved in his eyes.

“They were terribly apologetic, they did their best.”

“What happened to them?”

“We cut contact . . . that’s regulation number one. We have to protect ourselves.”

He nodded, looking away. “Will they ever go back?”

“I don’t know. Maybe, someday.” She leaned against the doorway. “But that’s why Mactav hates men; men, and war—and combined with the old taboo ... I guess her memory suppressors weren’t enough.”

Nilgiri reappeared beside them. “All better.” Her hands were bright pink. “Ready for anything!”

“How’s Mactav acting?”

“Super-solicitous. She’s still pretty upset about it, I guess.”

Light flickered at the curving junctures of the walls, ceiling, 'floor. Maris glanced up. “Hell, it’s getting dark outside. I expect I’d better be leaving; nearly time to open up. One last night on the town?” Nilgiri grinned and nodded; he saw Brandy hesitate.

“Maybe I’d better stay with Mactav tonight, if she’s still upset. She’s got to be ready to go up tomorrow.” Almost-guilt firmed resolution on her face.

“Well ... I could stay, if you think—” Nilgiri looked unhappy.

“No. It’s my fault she’s like this; I’ll do it. Besides, I’ve been out having a fantastic day, I’d be too tired to do it right tonight. You go on in. Thank you, Maris! I wish it wasn’t over so soon.” She turned back to him, beginning to put her hair into braids; quicksilver shone.

“The pleasure was all mine.” The tight sense of loss dissolved in warmth. “I can’t remember a better one either ... or more exciting—” He grimaced.

She smiled and took his hands; Nilgiri glanced back and forth between them. “I’ll see you to the lock.”

Nilgiri climbed down through the glow to the waiting flyer. Maris braced back from the top rung to watch Brandy’s face, bearing a strange expression, look down through whipping strands of loose hair. “Good-bye, Maris.”

“Good-bye, Brandy.”

“It was a short two weeks, you know?”

“I know.”

“I like New Piraeus better than anywhere; I don’t know why.”

“I hope it won’t be too different when you get back.”

“Me too. . . . See you in three years?”

“Twenty-five.”

“Oh, yeah. Time passes so quickly when you’re having fun—” Almost true, almost not. A smile flowered.

“Write while you’re away. Poems, that is.” He began to climb down, slowly.

“I will . . . Hey, my stuff is at—”

“I’ll send it back with Nilgiri.” He settled behind the controls, the flyer grew bright and began to rise. He waved; so did Nilgiri. He watched her wave back, watched her in his mirror until she became the vast and gleaming pearl that was the Who Got Her— 709. And felt the gap that widened between their lives, more than distance, more than time.

* * * *

“Well, now that you’ve seen it, what do you think?”

Late afternoon, first day, fourth visit, seventy-fifth year . . . mentally he tallied. Brandy stood looking into the kitchen. “It’s— different.”

“I know. It’s still too new; I miss the old wood beams. They were rotting, but I miss them. Sometimes I wake up in the morning and don’t know where I am. But I was losing my canyon.”

She looked back at him, surprising him with her misery. “Oh . . . At least they won’t reach you for a long time, out here.”

“We can’t walk home anymore, though.”

“No.” She turned away again. “All—all your furniture is built in?”

“Um. It’s supposed to last as long as the house.”

“What if you get tired of it?”

He laughed. “As long as it holds me up, I don’t care what it looks like. One thing I like, though—” He pressed a plate on the wall, looking up. “The roof is polarized. Like your ship. At night you can watch the stars.”

“Oh!” She looked up and back, he watched her mind pierce the high cloud-fog, pierce the day, to find stars. “How wonderfull I’ve never seen it anywhere else.”

It had been his idea, thinking of her. He smiled.

“They must really be growing out here, to be doing things like this now.” She tried the cushions of a molded chair. “Hmm . . .”

“They’re up to two and a half already, they actually do a few things besides mining now. The Inside is catching up, if they can bring us this without a loss. I may even live to see the day when we’ll be importing raw materials, instead of filling everyone else’s mined-out guts. If there’s anything left of Oro by then . . .”

“Would you stay to see that?”

“I don’t know.” He looked at her. “It depends. Anyway, tell me about this trip?” He stretched out on the chain-hung wall seat. “You know everything that’s new with me already: one house.” And waited for far glory to rise up in her eyes.

They flickered down, stayed the color of fog. “Well—some good news, and some bad news, I guess.”

“Like how?” Feeling suddenly cold.

“Good news—” her smile warmed him—“I’ll be staying nearly a month this time. We’ll have more time to—do things, if you want to.”

“How did you manage that?” He sat up.

“That’s more good news. I have a chance to crew on a different ship, to get out of the Quadrangle and see things I’ve only dreamed of, new worlds—”

“And the bad news is how long you’ll be gone.”

“Yes.”

“How many years?”

“It’s an extended voyage, following up trade contacts; if we’re lucky, we might be back in the stellar neighborhood in thirty-five years . . . thirty-five years tau—more than two hundred, here. If we’re not so lucky, maybe we won’t be back this way at all.”

“I see.” He stared unblinking at the floor, hands knotted between his knees. “It’s—an incredible opportunity, all right . . . especially for your poetry. I envy you. But I’ll miss you.”

“I know.” He saw her teeth catch her lip. “But we can spend time together, we’ll have a lot of time before I go. And—well, I’ve brought you something, to remember me.” She crossed the room to him.

It was a star, suspended burning coldly in scrolled silver by an artist who knew fire. Inside she showed him her face, laughing, full of joy.

“I found it on Treone . . . they really are in renaissance. And I liked that holo, I thought you might—”

Leaning across silver he found the silver of her hair, kissed her once on the mouth, felt her quiver as he pulled away. He lifted the woven chain, fixed it at his throat. “I have something for you, too.”

He got up, returned with a slim book the color of red wine, put it in her hands.

“My poems!”

He nodded, his fingers feeling the star at his throat. “I managed to get hold of two copies—it wasn’t easy. Because they’re too well known now; the spacers carry them, they show them but they won’t give them up. You must be known on more worlds than you could ever see.”

“Oh, I hadn’t even heard . . .” She laughed suddenly. “My fame preceded me. But next trip—” She looked away. “No. I won’t be going that way anymore.”

“But you’ll be seeing new things, to make into new poems.” He stood, trying to loosen the tightness in his voice.

“Yes . . . Oh, yes, I know . .

“A month is a long time.”

A sudden sputter of noise made them look up. Fat dapples of rain were beginning to slide, smearing dust over the flat roof.

“Rain! not fog; the season’s started.” They stood and watched the sky fade overhead, darken, crack and shudder with electric light. The rain fell harder, the ceiling rippled and blurred; he led her to the window. Out across the smooth folded land a liquid curtain billowed, slaking the dust-dry throat of the canyons, renewing the earth and the spiny tight-leafed scrub. “I always wonder if it’s ever going to happen. It always does.” He looked at her, expecting quicksilver, and found slow tears. She wept silently, watching the rain.

For the next two weeks they shared the rain, and the chill bright air that followed. In the evenings she went out, while he stood behind the bar, because it was the last time she would have leave with the crew of the Who Got Her. But every morning he found her sleeping, and every afternoon she spent with him. Together .they traced the serpentine alleyways of the shabby, metamorphosing lower city, or roamed the docks with the windburned fisherfolk. He took her to meet Makerrah, whom he had seen as a boy mending nets by hand, as a fishnet-clad Tail courting spacers at the Tin Soldier, as a sailor and fisherman, for almost forty years. Makerrah, now growing heavy and slow as his wood-hulled boat, showed it with pride to the sailor from the sky; they discussed nets, eating fish.

“This world is getting old. . . .” Brandy had come with him to the bar as the evening started.

Maris smiled. “But the night is young.” And felt pleasure stir with envy.

“True true—” Pale hair cascaded as her head bobbed. “But, you know, when ... if I was gone another twenty-five years, I probably wouldn’t recognize this street. The Tin Soldier really is the only thing that doesn’t change.” She sat at the agate counter, face propped in her hands, musing.

He stirred drinks. “It’s good to have something constant in your life.”

“I know. We appreciate that too, more than anybody.” She glanced away, into the dark-raftered room. “They really always do come back here first, and spend more time in here . . . and knowing that they can means so much: that you’ll be here, young and real and remembering them.” A sudden hunger blurred her sight.

“It goes both ways.” He looked up.

“I know that, too. . . . You know, I always meant to ask: why did you call it the ‘Tin Soldier’? I mean, I think I see . . . but why ‘tin’?”

“Sort of a private joke, I guess. It was in a book of folk tales I read, Andersen’s Fairy Tales”—he looked embarrassed—“I’d read everything else. It was a story about a toy shop, about a tin soldier with one leg, who was left on the shelf for years. . . . He fell in love with a toy ballerina who only loved dancing, never him. In the end, she fell into the fire, and he went after her—she burned to dust, heartless; he melted into a heart-shaped lump. . . .” He laughed carefully, seeing her face. “A footnote said sometimes the story had a happy ending; I like to believe that.”

She nodded, hopeful. “Me too— Where did your stone bar come from? It’s beautiful; like the edge of the Pleiades, depths of mist.”

“Why all the questions?”

“I’m appreciating. I’ve loved it all for years, and never said anything. Sometimes you love things without knowing it, you take them for granted. It’s wrong to let that happen ... so I wanted you to know.” She smoothed the polished stone with her hand.

He joined her tracing opalescences. “It’s petrified wood—some kind of plant life that was preserved in stone, minerals replaced its structure. I found it in the desert.”

“Desert?”

“East of the mountains. I found a whole canyon full of them. It’s an incredible place, the desert.”

“I’ve never seen one. Only heard about them, barren and deadly; it frightened me.”

“While you cross the most terrible desert of them all?—between the stars.”

“But it’s not barren.”

“Neither is this one. It’s winter here now, I can take you to see the trees, if you’d like it.” He grinned. “If you dare.”

Her eyebrows rose. “I dare! We could go tomorrow, I’ll make us a lunch.”

“We’d have to leave early, though. If you were wanting to do the town again tonight . . .”

“Oh, that’s all right; I’ll take a pill.”

“Hey—”

She winced. “Oh, well ... I found a kind I could take. I used them all the time at the other ports, like the rest.”

“Then why—”

“Because I liked staying with you. I deceived you, now you know, true confessions. Are you mad?”

His face filled with astonished pleasure. “Hardly ... I have to .admit, I used to wonder what—”

“Sol-dier!” He looked away, someone gestured at him across the room. “More wine, please!” He raised a hand.

“Brandy, come on, there’s a party—”

She waved. “Tomorrow morning, early?” Her eyes kept his face.

“Uh-huh. See you—”

“—later.” She slipped down and was gone.

The flyer rose silently, pointing into the early sun. Brandy sat beside him, squinting down and back through the glare as New Piraeus grew narrow beside the glass-green bay. “Look, how it falls behind the hills, until all you can see are the land and the sea, and no sign of change. It’s like that when the ship goes up, but it happens so fast you don’t have time to savor it.” She turned back to him, bright-eyed. “We go from world to world but we never see them; we’re always looking up. It’s good to look down, today.”

They drifted higher, rising with the climbing hills, until the rumpled olive-red suede of the seacoast grew jagged, blotched greenblack and gray and blinding white.

“Is that really snow?” She pulled at his arm, pointing.

He nodded. “We manage a little.”

“I’ve only seen snow once since I left Calicho, once it was winter on Treone. We wrapped up in furs and capes even though we didn’t have to, and threw snowballs with the Tails. . . . But it was cold most of the year on our island, on Calicho—we were pretty far north, we grew special kinds of crops . . . and us kids had hairy hornbeasts to plod around on. . . Lost in memories, she rested against his shoulder; while he tried to remember a freehold on Glatte, and snowy walls became jumbled whiteness climbing a hill by the sea.

They had crossed the divide; the protruding batholith of the peaks degenerated into parched, crumbling slopes of gigantic rubble. Ahead of them the scarred yellow desolation stretched away like an infinite canvas, into mauve haze. “How far does it go?”

“It goes on forever. . . . Maybe not this desert, but this merges into others that merge into others—the whole planet is a desert, hot or cold. It’s been desiccating for eons; the sun’s been rising off the main sequence. The sea by New Piraeus is the only large body of free water left now, and that’s dropped half an inch since I’ve been here. The coast is the only habitable area, and there aren’t many towns there even now.”

“Then Oro will never be able to change too much.”

“Only enough to hurt. See the dust? Open-pit mining, for seventy kilometers north. And that’s a little one.”

He took them south, sliding over the eroded face of the land to twist through canyons of folded stone, sediments contorted by the palsied hands of tectonic force; or flashing across pitted flatlands lipping on pocket seas of ridged and shadowed blow-sand.

They settled at last under a steep out-curving wall of frescoed rock layered in red and green. The wide, rough bed of the sandy wash was pale in the chill glare of noon, scrunching underfoot as they began to walk. Pulling on his leather jacket, Maris showed her the kaleidoscope of ages left tumbled in stones over the hills they climbed, shouting against the lusty wind of the ridges. She cupped them in marveling hands, hair streaming like silken banners past her face; obligingly he put her chosen few into his pockets. “Aren’t you cold?” He caught her hand.

“No, my suit takes care of me. How did you ever learn to know all these, Maris?”

Shaking his head, he began to lead her back down. “There’s more here than I’ll ever know. I just got a mining tape on geology at the library. But it made it mean more to come out here . . . where you can see eons of the planet laid open, one cycle settling on another. To know the time it took, the life history of an entire world: it helps my perspective, it makes me feel—young.”

“We think we know worlds, but we don’t, we only see people: change and pettiness. We forget the greater constancy, tied to the universe. It would humble our perspective, too-—” Pebbles boiled and clattered; her hand held his strongly as his foot slipped. He looked back, chagrined, and she laughed. “You don’t really have to lead me here, Maris. I was a mountain goat on Calicho, and I haven’t forgotten it all.”

Indignant, he dropped her hand. “You lead.”

Still laughing, she led him to the bottom of the hill.

And he took her to see the trees. Working their way over rocks up the windless branch wash, they rounded a bend and found them, tumbled in static glory. He heard her indrawn breath. “Oh, Maris—” Radiant with color and light she walked among them, while he wondered again at the passionless artistry of the earth. Amethyst and agate, crystal and mimicked wood-grain, hexagonal trunks split open to bare subtleties of mergence and secret nebulosities. She knelt among the broken bits of limb, choosing colors to hold up to the sun.

He sat on a trunk, picking agate pebbles. “They’re sort of special friends of mine; we go down in time together, in strangely familiar bodies. . . .” He studied them with fond pride. “But they go with more grace.”

She put her colored chunks on the ground. “No ... I don’t think so. They had no choice.”

He looked down, tossing pebbles.

“Let’s have our picnic here.”

They cleared a space and spread a blanket, and picnicked with the trees. The sun warmed them in the windless hollow, and he made a pillow of his jacket; satiated, they lay back head by head, watching the cloudless green-blue sky.

“You pack a good lunch.”

“Thank you. It was the least I could do”—her hand brushed his arm; quietly his fingers tightened on themselves—“to share your secrets; to learn that the desert isn’t barren, that it’s immense, timeless, full of—mysteries. But no life?”

“No—not anymore. There’s no water, nothing can live. The only things left are in or by the sea, or they’re things we’ve brought. Across our own lifeless desert-sea.”

“ ‘Though inland far we be, our souls have sight of that immortal sea which brought us hither.’ ” Her hand stretched above him, to catch the sky.

“Wordsworth. That’s the only thing by him I ever liked much.”

They lay together in the warm silence. A piece of agate came loose, dropped to the ground with a clink; they started.

“Maris—”

"Hmm?”

“Do you realize we’ve known each other for three-quarters of a century?”

“Yes. . . .”

“I’ve almost caught up with you, I think. I’m twenty-seven. Soon I’m going to start passing you. But at least—now you’ll never have to see it show.” Her fingers touched the rusty curls of his hair.

“It would never show. You couldn’t help but be beautiful.”

“Maris . . . sweet Maris.”

He felt her hand clench in the soft weave of his shirt, move in caresses down his body. Angrily he pulled away, sat up, half his face flushed. “Damn—!”

Stricken, she caught at his sleeve. “No, no—” Her eyes found his face, gray filled with grief. “No . . . Maris . . . I—want you.” She unsealed her suit, drew blue-silver from her shoulders, knelt before him. “I want you.”

Her hair fell to her waist, the color of warm honey. She reached out and lifted his hand with tenderness; slowly he leaned forward, to bare her breasts and her beating heart, felt the softness set fire to his nerves. Pulling her close, he found her lips, kissed them long and longingly; held her against his own heart beating, lost in her silken hair. “Oh, God, Brandy . . .”

“I love you, Maris ... I think I’ve always loved you.” She clung to him, cold and shivering in the sunlit air. “And it’s wrong to leave you and never let you know.”

And he realized that fear made her tremble, fear bound to her love in ways he could not fully understand. Blind to the future, he drew her down beside him and stopped her trembling with his joy.

In the evening she sat across from him at the bar, blue-haloed with light, sipping brandy. Their faces were bright with wine and melancholy bliss.

“I finally got some more brandy, Brandy ... a couple of years ago. So we wouldn’t run out. If we don’t get to it, you can take it with you.” He set the dusty red-splintered bottle carefully on the bar.

“You could save it, in case I do come back, as old as your grandmaw, and in need of some warmth. . . .” Slowly she rotated her glass, watching red leap up the sides. “Do you suppose by then my poems will have reached Home? And maybe somewhere Inside, Ntaka will be reading me.”

“The Outside will be the Inside by then. . . . Besides, Ntaka’s probably already dead. Been dead for years.”

“Oh. I guess.” She pouted, her eyes growing dim and moist. “Damn, I wish ... I wish.”

“Branduin, you haven’t joined us yet tonight. It is our last together.” Harkane appeared beside her, lean dark face smiling in a cloud-mass of blued white hair. She sat down with her drink.

“I’ll come soon.” Clouded eyes glanced up, away.

“Ah, the sadness of parting keeps you apart? I know.” Harkane nodded. “We’ve been together so long; it’s hard, to lose another family.” She regarded Maris. “And a good bartender must share everyone’s sorrows, yes, Soldier—? But bury his own. Oh—they would like some more drinks—”

Sensing dismissal, he moved aside; with long-practiced skill he became blind and deaf, pouring wine.

“Brandy, you are so unhappy—don’t you want to go on this other voyage?”

“Yes, I do—! But . .