I

The Nazi assault on the Jews in the first months of 1933 was the first step in a longer-term process of removing them from German society. By the summer of 1933 this process was well under way. It was the core of Hitler’s cultural revolution, the key, in the Nazi mind, to the wider cultural transformation of Germany that was to purge the German spirit of ‘alien’ influences such as communism, Marxism, socialism, liberalism, pacifism, conservatism, artistic experimentation, sexual freedom and much more besides. All of these influences were ascribed by the Nazis to the malign influence of the Jews, despite massive evidence to the contrary. Excluding the Jews from the economy, from the media, from state employment and from the professions was thus an essential part of the process of redeeming and purifying the German race, and preparing it to wreak its revenge on those who had humiliated it in 1918. When Hitler and Goebbels talked that summer of the ‘National Socialist Revolution’, this was in the first place what they meant: a cultural and spiritual revolution in which all things ‘un-German’ had been ruthlessly suppressed.

Yet the extraordinary speed with which this transformation had been achieved suggested at the same time powerful continuities with the recent past. Between 30 January and 14 July 1933, after all, the Nazis had translated Hitler’s Chancellorship in a coalition government dominated by non-Nazi conservatives into a one-party state in which even the conservatives no longer had any separate representation. They had coordinated all social institutions, apart from the Churches and the army, into a vast and still inchoate structure run by themselves. They had purged huge swathes of culture and the arts, the universities and the educational system, and almost every other area of German society, of everyone who was opposed to them. They had begun their drive to push out the Jews onto the margins of society, or force them to emigrate. And they were starting to put in place the laws and policies that would determine the fate of Germany and its people, and more besides, over the coming years. Some had imagined that the coalition installed on 30 January 1933 would fall apart like other coalitions before it, within a few months. Others had written off the Nazis as a transient phenomenon that would quickly disappear from the stage of world history together with the capitalist system that had put them in power. All of them had been proved wrong. The Third Reich had come into being by the summer of 1933, and it was clearly there to stay. How, then, did this revolution occur? Why did the Nazis meet with no effective opposition in their seizure of power?

The coming of the Third Reich essentially happened in two phases. The first ended with Hitler’s nomination as Reich Chancellor on 30 January 1933. This was no ‘seizure of power’. Indeed, the Nazis themselves did not use this term to describe the appointment, since it smacked of an illegal putsch. They were still careful at this stage to refer to an ‘assumption of power’ and to call the coalition a ‘government of national renewal’ or, more generally, a government of ‘national uprising’, depending on whether they wished to stress the legitimacy of the cabinet’s appointment by the President or the legitimacy of its supposed backing by the nation.118 The Nazis knew that Hitler’s appointment was the beginning of the process of conquering power, not the end. Nevertheless, had it not happened, the Nazi Party might well have continued to decline as the economy gradually recovered. Had Schleicher been less politically incompetent, he might have established a quasi-military regime, ruling through President Hindenburg’s power of decree and then, when Hindenburg, who was in his late eighties, eventually died, ruling in his own right, possibly with a revised constitution still giving a role of sorts to the Reichstag. By the second half of 1932, a military regime of some description was the only viable alternative to a Nazi dictatorship. The slide away from parliamentary democracy into an authoritarian state ruling without the full and equal participation of the parties or the legislatures had already begun under Brüning. It had been massively and deliberately accelerated by Papen. After Papen, there was no going back. A power vacuum had been created in Germany which the Reichstag and the parties had no chance of filling. Political power had seeped away from the legitimate organs of the constitution onto the streets at one end, and into the small cabal of politicians and generals surrounding President Hindenburg at the other, leaving a vacuum in the vast area between, where normal democratic politics take place. Hitler was put into office by a clique around the President; but they would not have felt it necessary to put him there without the violence and disorder generated by the activities of the Nazis and the Communists on the streets.119

In such a situation, only force was likely to succeed. Only two institutions possessed it in sufficient measure. Only two institutions could operate it without arousing even more violent reactions on the part of the mass of the population: the army and the Nazi movement. A military dictatorship would most probably have crushed many civil freedoms in the years after 1933, launched a drive for rearmament, repudiated the Treaty of Versailles, annexed Austria and invaded Poland in order to recover Danzig and the Polish Corridor that separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany. It might well have used the recovery of German power to pursue further international aggression leading to a war with Britain and France, or the Soviet Union, or both. It would almost certainly have imposed severe restrictions on the Jews. But it is unlikely on balance that a military dictatorship in Germany would have launched the kind of genocidal programme that found its culmination in the gas chambers of Auschwitz and Treblinka.120

A military putsch could, as many feared, have led to violent resistance by the Nazis as well as the Communists. Restoring order would have caused massive bloodshed, leading perhaps to civil war. The army was as anxious to avoid this as the Nazis. Both parties knew that their prospects of success if they tried to seize power alone were dubious, to say the least. The logic of co-operation was therefore virtually inescapable; the only question was what form co-operation would eventually take. All over Europe, conservative elites, armies, and radical, fascist or populist mass movements faced the same dilemma. They solved it in a variety of ways, giving the edge to military force in some countries, like Spain, and to fascist movements in others, like Italy. In many countries in the 1920s and 1930s, democracies were being replaced by dictatorships. What happened in Germany in 1933 did not seem so exceptional in the light of what had already happened in countries such as Italy, Poland, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Portugal, Yugoslavia or indeed in a rather different way in the Soviet Union. Democracy was soon to be destroyed in other countries, too, such as Austria and Spain. In such countries, political violence, rioting and assassination had been common at various periods since the end of the First World War; in Austria, for instance, serious disturbances in Vienna had culminated in the burning down of the Palace of Justice in 1927; in Yugoslavia, Macedonian assassination squads were causing havoc in the political world; in Poland, a major war with the nascent Soviet Union had crippled the political system and the economy and opened the way to the military dictatorship of General Pilsudski. Everywhere, too, the authoritarian right shared most if not all of the antisemitic beliefs and conspiracy theories that animated the Nazis. The Hungarian government of Admiral Miklós Horthy yielded little to the German far right in its hatred of Jews, fuelled by the experience of the short-lived revolutionary regime led by the Jewish Communist Béla Kun in 1919. The Polish military regime of the 1930s was to impose severe restrictions on the country’s large Jewish population. Seen in the European context of the time, neither the political violence of the 1920s and early 1930s, nor the collapse of parliamentary democracy, nor the destruction of civil liberties, would have appeared particularly unusual to a dispassionate observer. Nor was everything that subsequently happened in the history of the Third Reich made inevitable by Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor. Chance and contingency were to play their part here, too, as they had before.121

Nevertheless, the consequences of the events of 30 January 1933 in Germany were more serious by far than the consequences of the collapse of democracy elsewhere in Europe. The security provisions of the Treaty of Versailles had done nothing to alter the fact that Germany was still Europe’s most powerful, most advanced and most populous country. Nationalist dreams of territorial aggrandisement and conquest were present in other authoritarian regimes like Poland and Hungary as well. But these, if realized, were only likely to be of regional significance. What happened in Germany was likely to have a far wider impact than what happened in a small country like Austria, or an impoverished land like Poland. Its significance, given Germany’s size and power, had the potential to be worldwide. That is why the events of the first six and a half months of 1933 were so momentous.

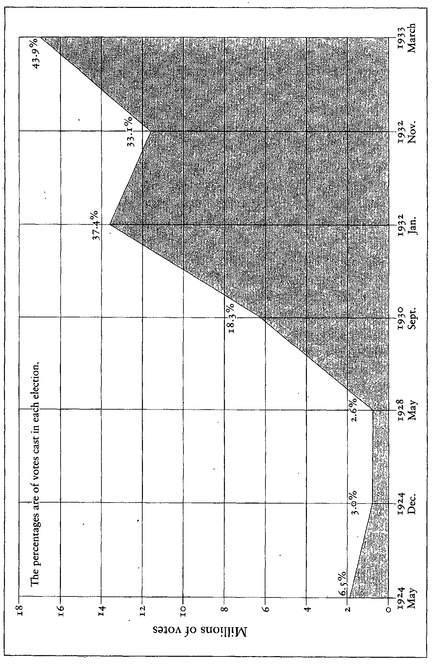

How and why did they occur? To begin with, no one would have thought it worth their while shoehorning Hitler into the Reich Chancellery had he not been the leader of Germany’s largest political party. The Nazis, of course, never won a majority of the vote in a free election: 37.4 per cent was all they could manage in their best performance, the Reichstag election of July 1932. Still, this was a high vote by any democratic standards, higher than many democratically elected governments in other countries have achieved since. The roots of the Nazis’ success lay in the failure of the German political system to produce a viable, nationwide conservative party uniting both Catholics and Protestants on the right; in the historic weakness of German liberalism; in the bitter resentments of almost all Germans over the loss of the war and the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles; in the fear and disorientation provoked in many middle-class Germans by the social and cultural modernism of the Weimar years, and the hyperinflation of 1923. The lack of legitimacy of the Weimar Republic, which for most of its existence never enjoyed the support of a majority of the deputies in the Reichstag, added to these influences and encouraged nostalgia for the old Reich and the authoritarian leadership of a figure like Bismarck. The myth of the ‘spirit of 1914’ and the ‘front generation’, particularly strong among those too young to have fought in the war, fuelled a strong desire for national unity and an impatience with the multiplicity of parties and the endless compromises of political negotiations. The legacy of the war also included political violence on a massive and destructive scale and helped persuade many non-violent and respectable people to tolerate it to a degree that would be unthinkable in an effectively functioning parliamentary democracy.

A number of key factors, however, stand out from all the rest. The first is the effect of the Depression, which radicalized the electorate, destroyed or deeply damaged the more moderate parties and polarized the political system between the ‘Marxist’ parties and the ‘bourgeois’ groups, all of which moved rapidly towards the far right. The ever-growing threat of Communism struck fear into the hearts of bourgeois voters and helped shift political Catholicism towards authoritarian politics and away from democracy, just as it did in other parts of Europe. Business failures and financial disasters helped convince many captains of industry and leaders of agriculture that the power of the trade unions had to be curbed or even destroyed. The political effects of the Depression hugely magnified those of the previous catastrophe of the hyperinflation, and made the Republic seem as if it could deliver nothing but economic disaster. Even without the Depression, Germany’s first democracy seemed doomed; but the onset of one of history’s worst economic slumps pushed it beyond the point of no return. Moreover, mass unemployment undermined Germany’s once-strong labour movement, a solid guarantor of democracy as recently as 1920, when it had managed to defeat the right-wing Kapp putsch despite the toleration of the rebels by the army. Divided and demoralized, and robbed of its key weapon of the political mass strike, the German labour movement was caught between impotent support for the authoritarian regime of Heinrich Brüning on the one hand, and self-destructive hostility to ‘bourgeois democracy’ on the other.

Figure I. The Nazi Vote in Reichstag Elections, 1924-1933

The second major factor was the Nazi movement itself. Its ideas evidently had a wide appeal to the electorate, or at least were not so outrageous as to put them off. Its dynamism promised a radical cure for the Republic’s ills. Its leader Adolf Hitler was a charismatic figure who was able to drum up mass electoral support by the vehemence of his rhetorical denunciations of the unloved Republic, and to convert this into political office, finally, by making the right moves at the right time. Hitler’s refusal to enter a coalition government in any other capacity but Reich Chancellor, a refusal that was terminally frustrating to some of his subordinates like Gregor Strasser, was proved right in the end. As deputy to the unpopular Papen or the equally unloved Schleicher, he would have lost heavily in reputation and surrendered a good deal of the charisma that came from being the Leader. The Nazi Party was a party of protest, with not much of a positive programme, and few practical solutions to Germany’s problems. But its extremist ideology, adapted and sometimes veiled according to circumstance and the nature of the particular group of people to whom it was appealing, tapped into a sufficient number of pre-existing popular German beliefs and prejudices to make it seem to many well worth supporting at the polls. For such people, desperate times called for desperate measures; for many more, particularly in the middle classes, the vulgar and uneducated character of the Nazis seemed sufficient guarantee that Hitler’s coalition partners, well educated and well bred, would be able to hold him in check and curb the street violence that seemed such an unfortunate, but no doubt temporary, accompaniment of the movement’s rise to prominence.

The substantial overlap between the Nazis’ ideology and that of the conservatives, even, to a considerable extent, that of German liberals, was a third major factor in bringing Hitler into the Reich Chancellery on 30 January 1933. The ideas that were current among almost all German political parties right of the Social Democrats in the early 1930s had a great deal in common with those of the Nazis. These ideas certainly bore enough resemblance to the Nazis’ for the bulk of the liberal and conservative parties’ supporters in the Protestant electorate to desert them, at least temporarily, for what looked like a more effective alternative. Nor were Catholic voters, and their representative, the Centre Party, any more committed to democracy by this time either. Moreover, even a substantial number of Catholics and workers, or at least those who for whatever reason were not as closely bound into their respective cultural-political milieu as the bulk of their fellows, turned to Nazism too. Only by striking a chord with pre-existing, often deep-seated social and political values could the Nazis rise so rapidly to become the largest party in Germany. At the same time, however, Nazi propaganda, for all its energy and sophistication, did not manage to win round people who were ideologically disinclined to vote for Hitler. Chronically underfunded for most of the time, and so unable to develop its full range of methods, excluded until 1933 from using the radio, and dependent on the voluntary work of often chaotic and disorganized local groups of activists, Goebbels’s propaganda offensive from 1930 to 1932 was only one of a number of influences driving people to vote for the Nazis at the polls. Often, indeed, as in the rural Protestant north, they voted without having been reached by the Nazi propaganda machine at all. The Nazi vote was above all a protest vote; and, after 1928, Hitler, Goebbels and the Party leadership recognized this implicitly by removing most of their specific policies, in so far as they had any, from the limelight, and concentrating on a vague, emotional appeal that emphasized little more than the Party’s youth and dynamism, its determination to destroy the Weimar Republic, the Communist Party and the Social Democrats, and its belief that only through the unity of all social classes could Germany be reborn. Antisemitism, so prominent in Nazi propaganda in the 1920s, took a back seat, and had little influence in winning the Nazis support in the elections of the early 1930s. More important by far was the image the Party projected on the street, where the marching columns of stormtroopers added to the general image of disciplined vigour and determination that Goebbels sought to project.122

The Nazi propaganda effort, therefore, mainly won over people who were already inclined to identify with the values the Party claimed to represent, and who simply saw the Nazis as a more effective and more energetic vehicle than the bourgeois parties for putting them into effect. Many historians have argued that these values were essentially pre-industrial, or pre-modern. Yet this argument rests on a simplistic equation of democracy with modernity. The voters who flocked to the polls in support of Hitler, the stormtroopers who gave up their evenings to beat up Communists, Social Democrats, and Jews, the Party activists who spent their free time at rallies and demonstrations - none of these were sacrificing themselves to restore a lost past. On the contrary, they were inspired by a vague yet powerful vision of the future, a future in which class antagonisms and party-political squabbles would be overcome, aristocratic privilege of the kind represented by the hated figure of Papen removed, technology, communications media and every modern invention harnessed in the cause of the ‘people’, and a resurgent national will expressed through the sovereignty not of a traditional hereditary monarch or an entrenched social elite but of a charismatic leader who had come from nowhere, served as a lowly corporal in the First World War and constantly harped upon his populist credentials as a man of the people. The Nazis declared that they would scrape away foreign and alien encrustations on the German body politic, ridding the country of Communism, Marxism, ‘Jewish’ liberalism, cultural Bolshevism, feminism, sexual libertinism, cosmopolitanism, the economic and power-political burdens imposed by Britain and France in 1919, ‘Western’ democracy and much else. They would lay bare the true Germany. This was not a specific historical Germany of any particular date or constitution, but a mythical Germany that would recover its timeless racial soul from the alienation it had suffered under the Weimar Republic. Such a vision did not involve just looking back, or forward, but both.

The conservatives who levered Hitler into power shared a good deal of this vision. They really did look back with nostalgia to the past, and yearn for the restoration of the Hohenzollern monarchy and the Bismarckian Reich. But these were to be restored in a form purged of what they saw as the unwise concessions that had been made to democracy. In their vision of the future, everyone was to know their place, and the working classes especially were to be kept where they belonged, out of the political decision-making process altogether. But this vision cannot really be seen as pre-industrial or pre-modern, either. It was shared in large measure, for one thing, by many of the big industrialists who did so much to undermine Weimar democracy, and by many modern, technocratic military officers whose ambition was to launch a modern war with the kind of advanced military equipment that the Treaty of Versailles forbade them to deploy. Like other people at other times and in other places, the conservatives, as much as Hitler, manipulated and rearranged the past to suit their own present purposes. They cannot be reduced to expressions of ‘pre-industrial’ social groups. Many of them, from capitalist Junker landlords looking for new markets, to small retailers and white-collar workers whose means of support had not even existed before industrialization, were as much modern as they were traditional.123 It was these congruities in vision that persuaded men like Papen, Schleicher and Hindenburg that it would be worth legitimizing their rule by co-opting the mass movement of the Nazi Party into a coalition government whose aim was to erect an authoritarian state on the ruins of the Weimar Republic.

The death of democracy in Germany was part of a much broader European pattern in the interwar years; but it also had very specific roots in German history and drew on ideas that were part of a very specific German tradition. German nationalism, the Pan-German vision of the completion through conquest in war of Bismarck’s unfinished work of bringing all Germans together in a single state, the conviction of the superiority of the Aryan race and the threat posed to it by the Jews, the belief in eugenic planning and racial hygiene, the military ideal of a society clad in uniform, regimented, obedient and ready for battle—all this and much more that came to fruition in 1933 drew on ideas that had been circulating in Germany since the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Some of these ideas, in turn, had their roots in other countries or were shared by significant thinkers within them - the racism of Gobineau, the anticlericalism of Schonerer, the paganist fantasies of Lanz von Liebenfels, the pseudo-scientific population policies of Darwin’s disciples in many countries, and much more. But they came together in Germany in a uniquely poisonous mixture, rendered all the more potent by Germany’s pre-eminent position as the most advanced and most powerful state on the European Continent. In the years following the appointment of Hitler as Reich Chancellor, the rest of Europe, and the world, would learn just how poisonous that mixture could be.