nine

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

AND BEYOND

The First World War

When news reached Boston on Tuesday 4 August that the country was at war with Germany, the Boston Company of the Territorial Army – the former Rifle Volunteers – had already been ordered back to the town from their annual camp at Bridlington and by Tuesday evening they were assembled at their new drill hall on Main Ridge. The next day sixty soldiers of the East Yorkshire Cycle Corps arrived in the town, to be billeted in St John’s School. They were to guard the dock and other strategic points along the coast in the event of an attempted invasion. On the same day, the Boston Company, commanded by Meaburn Staniland, the town clerk, and one of the town’s ‘gallant eight’ who had fought in the Boer War, received their orders to march to Lincoln. On the Thursday they paraded through the town, with the Excelsior Brass Band leading the way, and an enormous and very patriotic crowd lined the streets to give them an emotional and enthusiastic send-off. The town’s other Territorial Army unit, the Artillery Battery, needed to purchase more horses to bring their unit up to strength, but by the following Tuesday they too were ready and, again accompanied by a cheering crowd and a brass band, they departed the town that day by train.1

From the start, there was considerable support for the war, much encouraged by the popular view that it would be ‘all over by Christmas’, and by lurid newspaper accounts of German atrocities committed against the civilians of ‘brave little Belgium’. Recruiting campaigns for Kitchener’s volunteer army got off to a slow start, however, and on the first day of the campaign, on 12 August, when a series of passionately patriotic and anti-German speeches were made in the Market Place, only four men came forward to ‘take the King’s shilling’. Boston was too small to be able to put together its own Pals’ Battalion – unlike Grimsby, where the ‘Chums’ were quickly recruited – and this was a major handicap for those trying to persuade the town’s young men to volunteer. Under enormous pressure from the local press, however, more and more gradually joined, and in mid-October it was reported that as many as 700 local men were serving in the armed forces. About seventy were in the regular army, about 390 were in the Territorials, and about 250 were volunteers for Kitchener’s army. The local newspapers had persuaded many of the latter that it was better to join up than be vilified as ‘skulking parasites’, ‘a curse to the country’ and members of ‘the White Feather Brigade’.

Hatred of Germany, coupled with fears of imminent invasion and a fear of spies, meant that the handful of Germans living in the town immediately became objects of profound suspicion. The town’s five German nationals were at first arrested and locked up in the Drill Hall, before being allowed to return home, provided they reported to the Boston police station every day. Ultimately, they would spend most of the war as prisoners, interned in a camp in Yorkshire. Two brothers, George and Leonard Cantenwine, who were pork butchers in the town, were also of German origin but had taken British nationality more than twenty years before. This did not prevent them, however, from also becoming objects of suspicion and hatred. On the very first Saturday night after the outbreak of war, a drunken mob chose to show their patriotism by smashing the Cantenwines’ shop windows and looting the contents. Fortunately, the police arrived quickly, a number of arrests were made and numerous rioters were fined. A few local people wrote to the local papers to express their sympathy for the Cantenwines, but the brothers continued to suffer distrust and resentment from many other residents. In January 1916, George Cantenwine was arrested and charged with signalling to a Zeppelin with flashing lights to direct its course, after allegations had been made by a group of drinkers coming out of the Witham Tavern. He was found not guilty because he could prove that he had not been in the house at the time, but in August 1918 an anonymous letter appeared in the local press accusing the Cantenwines of spying on the aerodrome at Freiston and of plotting to assist a German invasion. The Cantenwines sued the letter writer, who turned out to be a man of considerable local influence: Mr Joseph Bowser, a local Justice of the Peace, a farmer, and the chairman of the local branch of the NFU. The court ruled that the letter was defamatory, but awarded no damages and ordered the Cantenwines to pay all the court costs as it considered the letter to be ‘fair comment’ on a matter of national concern. Not surprisingly, the brothers shortly afterwards sold their shop and other property and left the area for ever.

The heavy casualties suffered during the first two years of the war meant that the government was obliged to introduce conscription in 1916. In the last months of 1915, however, the ‘Derby Scheme’ was introduced, under which those who had not yet volunteered could at least register their willingness to join the armed forces if required, and could thus be regarded as volunteers rather than as conscripts. This proved very popular in Boston, and about 1,000 Boston men and 500 from local villages flocked to the Drill Hall to attest their willingness before the scheme closed.

By the time the war ended in November 1918, approximately 6,000 men and women from Boston and the surrounding area had served in the war in one role or another. Altogether, 943 men and two women from the area lost their lives in the war: 435 from Boston and 510 from twenty-two nearby villages. The losses would have been even greater, however, had the two Boston Territorial units not been fortunate enough to avoid involvement in the bloodiest battles of 1916 and 1917, those of the Somme, Arras, Passchendaele and Cambrai. For Boston, the blackest week came in October 1915, when fifteen Boston men were killed and twenty-three were wounded in one day in an attack on the Hohenzollern Redoubt, as part of the Battle of Loos. Among other casualties earlier in the year – during the Second Battle of Ypres – both Captain Meaburn Staniland and his younger brother, Lieutenant Geoffrey Staniland, had been killed. Captain Staniland left a widow and four young children, who tragically also lost their mother in the following January to a combination of scarlet fever, German measles and, it was said, a broken heart.

There were also civilian casualties. The first Zeppelins were seen over Boston in January 1916, but no bombs were dropped as they made their way towards the towns of the East Midlands. On Saturday, 2 September, however, a Zeppelin dropped four bombs on the town, doing much damage, seriously wounding four people and killing Tom Oughton, the teenage son of the lock-keeper at the Grand Sluice Bridge. The raid caused considerable alarm and fear, while also exposing both the lack of clear blackout regulations and the absence of any local defence against Zeppelins. As a result of this, a battery of four 13-pounder anti-aircraft guns were set up in the town in January 1917, but the town suffered no more raids and they were withdrawn six months later.

The other civilian casualties of the war were the town’s fishermen. Ten Boston trawlers were sunk by the German navy in the North Sea in the first days of the war, their crews unaware that war had been declared. The fishermen were taken prisoner and most were to spend the duration of the war in rather miserable and unhealthy conditions; hungry, bored and often depressed. Following this, the Boston Deep Sea Fishing Company, which had owned nine of the trawlers, suspended all further fishing operations and laid off its remaining eighty fishermen. Fishing was resumed in 1915 but the Navy was unable to protect the trawlers from German submarines, and during the next three years six more trawlers were sunk, in some cases with all hands lost. By the end of the war fifty-one Boston fishermen had lost their lives, forty-seven as a result of enemy action at sea, and four had died while being held by the Germans as prisoners of war.

The disruption of the fishing industry was a major blow to the town’s economy and an important cause of the growth of unemployment in the first years of the war. Both the town’s coastal and international trade were badly affected, one long-established firm of shipping agents was forced to close, as was one of the town’s fish merchants, and the Peacock & Royal Hotel also went bankrupt. The bowling green of the old hotel was bought by its members, but the building itself became a hostel for women who had volunteered for the Women’s Land Army, and would not become a hotel again until after the war, when it was purchased by the Wainfleet family brewers, William Bateman & Sons.

Life on the Home Front was also made increasingly difficult by rising food prices, increases in taxation, and growing shortages of many essentials, including many food items and coal; especially from 1916, when German submarines proved very effective in sinking British merchant ships in the Atlantic. Shopping could prove an arduous and exhausting ordeal, as the Standard described in December 1917. When word got round that one shop had margarine for sale, shoppers rushed to buy but failed to form an orderly queue, and in the scramble for margarine many were disappointed and the successful ones emerged ‘with dishevelled dresses and with their headgear hanging in the region of their shoulders’. By 1918, anyone caught hoarding food could be fined, and from 1917 a number of local farmers were also fined for selling on the black market, above the prices set by the government. Some families were able to help make ends meet by growing their own food, a practice which the council encouraged by increasing the land available to be let as allotments. Children were also encouraged to help their families by picking potatoes. In 1917, 585 children from five of the town’s elementary schools picked 4,000 tons of potatoes from 400 acres, and were paid 2s per day.

There were also complaints in the newspapers about the behaviour and morals of some of the soldiers who were stationed in the town. Troops belonging to a company of the 2nd/6th Suffolk Regiment, who replaced the East Yorkshire Cycle Corps in 1915, were alleged to be responsible for an increase in the number of illegitimate births in the town in the latter years of the war, and a petition sent to the council in 1918, signed by fifty-eight local ladies, complained of a lowering of moral standards in the town. Soldiers are not specifically blamed but it would appear that they were held to be mainly responsible for what the ladies rather vaguely called ‘the present disgraceful conduct in the streets whereby a bad example is set to young people’. The petition claimed that, as a result of this, ‘respectable women have to avoid being out in the evenings’.

The War Memorial today, Bargate Green.

In November 1918, news that the war was finally over was greeted with much relief, as well as much rejoicing. Too many families had lost fathers, brothers, sons, close friends and sweethearts, and for many of those who grieved, life would never be the same again. But on the night of the Armistice, the blackout restrictions were lifted, the band of the Suffolk Company played in the Market Place, and a happy crowd danced and sang. One of the last casualties of the war would be a Boston man. Just a few hours before the ceasefire came into effect, Bombadier Stanley Lote of the Royal Field Artillery was shot in the head by a German sniper; he died six days later. His name, and the names of all those from the town who died in the war, were inscribed on the war memorial, erected in 1921 on Bargate Green.

The Interwar Years

The war had dealt a huge blow to the town’s economy, and particularly to the import-export business of the port – in which trade with Germany had played such an important part up to 1914 – and to the fishing industry. As the troops returned home in 1919 employment prospects seemed bleak, and it was little surprise to find in 1921 that the town’s population, which had been rising steadily for the last twenty years before the war, had fallen a little in the previous ten years, from 21,910 (including Skirbeck and Skirbeck Quarter) to 21,477. A brief post-war recovery in the early 1920s was then struck two further blows in 1926–27. Coal exports, which had been by far the largest commodity shipped from the town before the war, were still a long way from reaching pre-war levels when the industry was hit by the effects of the miners’ strike, and in 1926 exports of coal from the port fell below 100,000 tons, to their lowest level for about forty years. Then, in 1927, the town suffered another setback: the almost total loss of the fishing industry.2

This calamity, which threw a great many out of work almost overnight, came about when the owner of the Boston Deep Sea Fishing Company, Fred Parkes, decided to withdraw his trawlers from the town and relocate to Fleetwood, following a legal dispute with the corporation. Parkes deeply resented having to resort to threats of court action to obtain money he believed was owed his firm for its efforts to remove and salvage a ship that had gone aground in the Witham outfall a few years earlier. This dispute, however, was not the only cause of the company’s removal. At the time Parkes claimed that he had had no plans to leave the town before this but, when recalling the incident many years later, he admitted that he might well have withdrawn his business from the port in the next few years anyway. Changes in the costs involved in the trawling industry meant, he explained, that Boston’s geographical position was beginning to make it a less suitable location as a base for his company, and by the late 1920s its days as a deep-sea fishing port were therefore probably already numbered:

Boston was not so well suited as you might imagine; there was a long river to navigate and then the Wash, whereas, at a port like Lowestoft for example, the fishing vessels can come straight into the port direct from the fishing grounds which are only two or three hours away. Boston was never suitable for deep sea fishing from the distant grounds off Norway, Iceland, Greenland and elsewhere … The river at Boston and the long run up from the Wash lost valuable time; in those days when we could operate trawlers at about £10 per day it did not matter so much but today when our larger vessels cost anything from £200-£300 per day to run, time and distance saved counts.3

These were major blows to the town’s economy, and to employment in general, but to some extent their effects were alleviated in the years that followed by the growth of new industries, and particularly by the growth of the canning industry. While still in his teens, Wilfred Beaulah, the son of Alderman John Beaulah, set up the first fruit and vegetable canning business in the county in 1913 at the Maud Foster Mill, as a sideline to his father’s and uncle’s wholesale grocery business. This prospered rapidly, and by the 1930s it was the more profitable half of the Beaulah family business. Its success attracted rivals, and between 1930 and 1933 two more large canning firms were established in the town: United Canners, who opened their factory on Norfolk Street, just off the Horncastle Road in the north of the town, and Lincolnshire Canners, who established their factory at the opposite end of the town, on London Road, occupying the former Skirbeck Oil Mill built by J.C. Simonds in 1870. The new factories particularly boosted the employment of women, but working days were long. Until the passage of the 1937 Factory Act, which introduced the forty-eight hour week, many women worked sixty-hour weeks, and work could start as early as six o’clock.4

The town’s port also managed to expand its activities during the 1930s, in spite of the continuing low levels of coal exports. Timber imports from the Baltic countries increased, and half a dozen timber importers are listed in the 1937 directory. Railway sleepers remained an important aspect of this trade; they were discharged over the sides of the ships into the dock, put together to make thick rafts, and then floated down to a special slip at the inner end of the dock and taken to the Hall Hills sleeper depot. Fertiliser imports were also much increased by the development of fertiliser production in the town, and in 1936 the town’s combined imports were for the first time greater than her export of coal. Trade was also boosted by the shipping of partially refined sugar to London, produced at the newly opened Spalding beet factory. The port authorities were actually able to turn the removal of Parkes’ trawlers to good effect, as the whole of the dock’s facilities could now be used by all cargoes. The buildings and berths which had once been available only for the fishing industry were now adapted to be used by all shippers. And fishing did not entirely disappear from the port. Sufficient numbers of herrings were brought into the port for L. Braine & Sons to be running a specialist herring curing business in the High Street in the late 1930s, and at least two fish merchants specialised in distributing shellfish. Wholesale fruit importers also appear in the local directories for the first time in the 1920s and 1930s; a reflection partly of the demands of the town’s new canning industry. The port’s fortunes were also assisted by the development of road transport. By the 1930s, the majority of goods and materials shipped out of the port arrived by lorry, not by rail. By 1938, only 64,000 out of a total of 294,000 tons of freight entering the port did so by rail.5

In 1939 the coastal trade and the overseas trade of the port were roughly equal. In a typical week in 1939 eleven ships came into the port from other British ports, and seven left for coastal destinations, while nine arrived from overseas and eight left for foreign destinations. The ships undertaking overseas voyages tended to be larger than the coastal vessels, some of which were still powered principally by sail, and particularly the Thames spritsail barges, which continued to ply their way to Boston until after the Second World War, collecting beet, oilcake, and wheat. The last true sailing ship to be seen in Boston was the Danish three-masted schooner, Frida, which arrived empty from America, dropped her ballast on the bank at Freiston Shore, loaded 435 tons of coal in Boston dock, and sailed for Denmark on 18 February 1932. Owing to the port’s geographical position, overseas trade was still largely with northern Europe, and especially with the Dutch and Baltic ports.6

Most of Boston’s other larger employers also managed to survive throughout the 1920s and 1930s. One old firm that did disappear, however, was the cigar-making business of Thorns, Son & Co., which closed in 1928. The firm had been established in 1850 and was the last survivor of this industry in the town. The town’s other cigar makers, Whittle & Cope, had closed down in 1915. The label and luggage tag business of Fisher, Clark & Co., which had been established at about the same time as Thorns, grew steadily throughout the interwar years, and by 1938 employed 350 people. It was calculated that between 1902 – when the firm had first moved to Norfolk Street – and 1938, it had made twenty-one extensions. Other long established businesses that managed to survive in these difficult years included the bedding manufacturer Fogarty’s, and the seed firm of W.W. Johnson & Son, both of which would expand quite remarkably after the Second World War to become businesses of international importance.7

The town’s population was rising steadily again throughout the 1920s, and probably also rose throughout most of the 1930s as well, although in the absence of a national census until 1951 no reliable figures for this period are available. By 1931 it had risen to 22,845, and when the first census was completed after the Second World War, in 1951, it had risen again to 24,453.

Although many lives were blighted by unemployment, for those who were fortunate enough to remain in employment, the interwar years were in many respects a period of improving living standards. A new and much improved sewage system was finally installed for those living on the eastern side of the town in 1936, but those living on the other side of the river would have to wait another thirty years for similar improvements. Electric street lighting finally replaced the gas lamps in 1924 and an improved water supply for most inhabitants followed the council’s purchase of the local water company in 1931. The General Hospital was enlarged during these years and in 1922 a large house on London Road, which until very recently had been the ‘Home for Fallen Women’, was converted into a sanatorium for the treatment of those suffering from advanced tuberculosis, and enlarged in 1935. It would later become the London Road Hospital.

Communications between Boston and other Lincolnshire towns and villages were also much improved by the advances made in local bus transport. From the mid-1920s bus companies, including the south Lincolnshire-based Progressive Company, the Silver Queen Company (later the Lincolnshire Road Car Company) and Fred Wright of Louth, established services that linked Boston to other major towns in the county, and to all villages en route. By 1939 a comprehensive network of services linked every part of the county, and travel between towns and villages was far easier and quicker than it had ever been before. The horse-drawn carrier was rapidly disappearing, with just seven still recorded in 1937 serving the nearest villages, and it is a measure of the popularity and competitiveness of the buses that they were also beginning to take customers away from the railways for short-distance travel. They also assisted the trend, which was already well established, for more people to live outside the town in nearby villages and to commute into work, as the first morning buses from the nearest villages arrived in time for most people’s working day. Wyberton, just 2 miles to the south of the town, grew particularly rapidly from this time to become a commuter village. In the evenings, and at weekends, more people than ever before could now come into the town to enjoy the social and entertainment facilities it had to offer, such as a dance or public meeting in the Assembly Rooms, a play at the Shodfriars Hall, or a visit to one of the town’s cinemas or a football match.8

In 1919, the council purchased the private park to the north of Wide Bargate, by now known as Hopkins’ Park, and developed it as Central Park, with space and facilities for cricket and football and all the other games already enjoyed at the opposite end of the town, in People’s Park. Unfortunately, however, the need to extend the dock’s timber storage facilities in the 1930s led to the closure of the latter, although the nearby corporation swimming baths survived this development and remained in use for another thirty years.

Perhaps the most popular form of entertainment – and one of the newest – by this time was the cinema, and the arrival of the ‘talkies’ in the early 1930s only added to its popularity with both sexes, with both middle and working classes, and with all age groups. People often went at least twice a week and for many it would be unthinkable to miss the latest Hollywood film. The Premier Electric Theatre at the Corn Exchange and the Scala both continued to operate; the Electric Theatre even had a new (but not very imaginative) name – the ‘New Theatre’. With the ‘talkies’ came also larger and more comfortable cinemas, the Odeon and the Regal. For many children the highlight of the week was the Saturday afternoon matinee, and the ‘cowboys’ were especially popular; the likes of Tom Mix and Hoot Gibson were heroes who, whatever the odds, always came out on top.

The appeal of football was less all-embracing, but for many men and their sons, loyalty to the local football club was an important part of life. Two local teams, Boston Swifts and Boston Town, came together in 1918 to form Boston FC to compete in the local league. In 1933 it went into liquidation but a new club was almost immediately created to replace it – Boston United FC – which survives to this day. The popularity of both football and cricket was much encouraged by newspaper reports of matches between the more successful clubs, and both men and boys collected cigarette cards, featuring football and cricket heroes.

For the middle classes, golf remained very popular, and in 1925 the local club moved to a new nine-hole course on Fishtoft Road. Tennis was also rapidly growing in popularity and during the 1930s a Boston Lawn Tennis Club was established, with courts laid out on the Sleaford Road. There had long been a rowing club, an angling club and a bowls club in the town, and by 1937 there was also a rugby football club, with its headquarters appropriately located at a local inn, the White Hart Hotel. For increasing numbers of the wealthier middle classes, leisure could also now mean a holiday abroad, and shipping firm W. Bradley & Co., who had offices in the Corporation Buildings, had already begun to advertise their services as travel agents, as well as emigration agents, shortly before the First World War.9

The former Regal Cinema, West Street, today.

The appearance of the town changed little in these years. Further restoration work had to be carried out between 1928 and 1933 to strengthen the tower of St Botolph’s and to renew the roofs in the nave and aisles, but the great age of church and chapel building – which had been such an important feature of the town in the nineteenth century – was long past. Indeed, with falling memberships and shrinking congregations, the various Methodist churches sought union after 1918, and as part of this process the West Street New Connexion chapel closed in 1934. The site was shortly afterwards developed as the Regal Cinema. The only major new public building erected at this time was the County Hall, built for the Holland County Council, between 1925 and 1927, next to the Sessions House and, like the older building, also in the Gothic style. Astonishingly, Boston also almost lost one of its finest buildings in the early 1930s, when the dilapidated state of Fydell House led to proposals that it should be demolished. Fortunately the vicar, Malcolm Cook, who was also a keen local historian, organised a successful campaign to save the building, establishing in the process the Boston Preservation Trust, to buy the building in 1935. Fydell House would later become an Adult Education Centre, known as Pilgrim College, an outpost of Nottingham University. The ancient Guildhall, standing next door, had been converted into a museum in 1929. Its historic connections with the Pilgrim Fathers, as the courthouse where some of the leaders had been tried in 1607 and the site of their initial imprisonment, ensured a steady stream of visitors, including Americans. Links with America were strengthened further when the American Room was opened in Fydell House in 1938, and the opening ceremony was performed by the American ambassador, Joseph Kennedy.

Another very positive development in this period was the great improvement made in the educational opportunities for the girls of the town and the surrounding villages. With secondary education now the responsibility of Holland County Council, a grammar school for girls was finally opened in January 1921: the Boston High School for Girls. This occupied a large house, known as Allan House, on Carlton Road. The school opened with 112 girls, a staff of eight ladies including the headmistress, Miss Frances Mary Knipe, and five classrooms. In the following September the number rose to 180, but the school badly needed more space and better facilities. Some of the girls had to be taught at the former Pupil Teachers’ Centre and for three years games lessons had to be held across the town in the People’s Park, until a field could be hired from the council on Sleaford Road. Things improved a little in 1922 when a group of huts were erected in the school grounds, giving the school four extra classrooms, a science laboratory and an assembly hall, but the major step forward came in May 1939, when the girls and their teachers were able to move into new and much improved premises on Spilsby Road, where the school is still sited today. The idea of high quality girls’ education was still a novelty however, and there were many, including the editor of the Boston Guardian, who viewed the new school as ‘palatial’ and ‘far too lavish’. The County Council was also willing to spend money to improve the Boys’ Grammar School. In 1904 it had added a science block and in 1926 added a group of classrooms, built as a quadrangle behind the Tudor schoolhouse. By contrast, the Boston Corporation made no major improvements to the town’s elementary schools and, in spite of the Hadow Report’s recommendations in 1926, no attempt was made in the late 1920s or early 1930s to introduce ‘senior schools’, to give all children (as the Hadow Report had recommended) a secondary education. Eventually, in the late 1930s, proposals were made to build two new senior schools, but the plans had to be suspended owing to the outbreak of war.10

The Boston High School for Girls, Spilsby Road.

The Second World War

Unlike 1914, no celebrations greeted the news that Britain was once again at war with Germany in September 1939. When Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain broadcast to the nation on the morning of Sunday 3 September, the mood in Boston, as elsewhere in the country, was subdued. There was sadness that the sacrifices of the Great War had not, after all, brought lasting peace. There was also much fear of aerial bombing and gas attacks. But there was also a steely determination to succeed in meeting and overcoming whatever challenges the war was likely to present, and recognition that this war would involve everybody.11

To some extent, there was also relief that the waiting was over, for war against Germany had been expected for most of the previous year, ever since the Munich crisis of the previous autumn, when conflict had only been avoided at the last moment by the Munich Agreement, which had given Hitler almost everything he wanted at the expense of Czechoslovakia. Many preparations had already been made. Gas masks had been issued to everyone other than babies and very small children. A Chief Air Raid Warden had been appointed for the town and surrounding district, and the borough had been divided into ten areas under his control, with a team of volunteers appointed in each. Plans had also been drawn up for the evacuation of up to 4,000 children, teachers and pregnant women from the dock area of Hull to the Boston area, although the town itself was too likely a target for the German bombers to be a suitable place for evacuees. The evacuation began on the same Sunday that Chamberlain made his historic broadcast. One local lady, who saw the first evacuees arrive that morning, recalled one particular detail of their arrival: ‘They were taken first to a local school, Staniland School, to be processed and inspected for lice. Those with lice had a mark indicating this painted on their foreheads.’12

By that evening over 3,000 evacuees had been brought from Hull and allocated to their temporary homes in the villages surrounding Boston. Local people were shocked to see that some of the children, from the poorest parts of Hull, had only the most ragged, hand-me-down clothes to wear.

The long-established Boston Company, which had fought as part of the Territorial Army in the First World War, now became C Company of the 4th Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment. One of its officers was Jack Staniland, one of the four sons of Meaburn Staniland, who had been killed with the Boston Company in 1915. The company was ordered to report to the Main Ridge Drill Hall on 1 September, as soon as news came through of Germany’s invasion of Poland, but it was more than a month later that they finally marched to the station to take a train to Ripon to join the 49th West Riding Division. As in 1914, a brass band led the way and a large crowd cheered them as they passed through Boston’s streets.

Although there would be little fighting – except at sea – until Germany’s invasion of Denmark and Norway ended the ‘Phoney War’ in the following April, the impact of the war on the town was felt immediately. A total blackout was imposed, causing a big increase in road accidents and petty crime; many men spent long hours on ARP work; a new cottage industry was created – the making of camouflage netting – organised by fishing smack owner Sid Lovelace; and rationing was introduced within a fortnight of war being declared, first for petrol and then coal. Some people started building their own bomb shelters but the first public bomb shelters were erected in October, and at about the same time, identity cards were issued as a precursor to ration cards. Before Christmas, food rationing had begun.

When an official appeal was made to form a Local Defence Volunteer force, in May 1940, 300 men came forward immediately. The survival of the country now seemed to hang by a thread. German forces had swept into France and it seemed very likely that Britain’s only ally against Germany was about to fall. There were fears that the British army in France, the British Expeditionary Force, would also be soon trapped and lost. An attempted invasion of Britain was apparently imminent. Pill-boxes were erected, roadblocks were put up, trenches were dug and all road signs disappeared. Night after night, members of the LDV (soon to be called the ‘Home Guard’) stood guard on Rochford Tower, looking anxiously towards the coast.

Everyone could ‘do their bit’. The ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign, launched in late 1939, encouraged allotments and back garden (and sometimes even front garden) vegetable production and poultry keeping. As early as December 1939 the girls of the High School dug up 2 acres of the school grounds, setting an example soon to be followed by the golf club and many others. The various local village branches of the Women’s Institute organised jam-making on an enormous scale as a contribution to the country’s food supply. The record was probably set in the summer of 1943 when one woman alone from a nearby village made 745lbs of jam.

Mass conscription meant an end to unemployment and eventually a considerable improvement in wage levels, as labour was now so scarce. The Agricultural Workers’ Union, for instance, managed to double farm workers’ wages during the war. Those working in the canning factories found themselves on overtime rates and working flat out as the factories sought to meet war contracts. They also benefitted from greatly increased domestic demand for tinned fruit and vegetables, now that fresh food became much less available. A new factory also opened in Marsh Lane for dried potato production. Fear of invasion led the government to order the removal of Fisher Clark’s business to Macclesfield in 1940, causing considerable hardship, but when the fear lifted a year later the firm returned to Boston. Demand for anyone with engineering skills was also greater than ever as local engineering firms were, by 1942, much involved in fitting out flotillas of invasion barges. Nine were to be built at Boston, with twelve barges to a flotilla.

Many people participated in the savings campaigns, lending money to the government to spend on armaments, and the various salvage drives were also enthusiastically supported, especially for waste paper; in 1940 Boston was judged to have collected more paper per head of population than any other town in the country. Scrap metal, bones, rags and tin cans were also collected, and most of Boston’s iron railings, the 1918 tank that had stood near the war memorial, and heavy guns brought back from the Crimean War, were all sacrificed to the war effort.

Throughout the war there were many servicemen and women stationed in or near the town, including airmen at the nearby bomber airfields of Coningsby, Woodhall Spa and East Kirkby, and sailors and wrens stationed at St John’s House. This was the former Union Workhouse which the Navy took over to create HMS Arbella. By 1943, American soldiers and airmen were also much in evidence. ‘Overpaid, over-sexed and over here’, they made a considerable impact. Dances at the Gliderdrome and the Assembly Rooms had never been so popular, the town’s four cinemas were fully patronised, and romances between servicemen and local girls flourished.

The war changed many of life’s previously accepted rules. For the first time ever, to provide some entertainment for bored and lonely servicemen, cinemas were allowed to open on Sundays. Then, after a long debate, the council agreed that the tennis courts and bowling greens in Central Park could also open, although only between two and five o’clock, when there were no church services. The swimming baths were also very popular, cycling enjoyed a revival as a leisure activity and, with Skegness beach covered with barbed wire and mines, many families enjoyed instead a walk on Frampton Marsh or at Hobhole Drain. The first canteens for the forces opened in Dunkirk week, staffed by volunteers and paid for by local businessmen. The Guildhall became a British restaurant where civilians could also get cheap, off-ration meals, and so many mothers were now at work that a school meals service was introduced for the first time.

The loss of life as a result of the war was overall about half that of the First World War; 217 deaths compared to 435 in 1914–18. There were fewer deaths of those in the armed forces – in the First World War many soldiers’ lives had been needlessly thrown away in hopeless infantry assaults – but the number of civilian deaths was greater. The Boston Territorials, as part of the 4th Lincolns, were heavily involved in the Norway Campaign in April 1940. After taking up a forward position near Steinkjer, they found themselves cut off from the rest of the battalion and surrounded. They succeeded, however, in making an almost miraculous escape, marching by night in single file for almost 50 miles in deep snow to rejoin the battalion without losing a single soldier. Nevertheless, two Boston men were killed in the Norway Campaign, and further local casualties followed in the retreat of the BEF from France in the following month, and in the evacuation from Dunkirk. Two Boston airmen and five soldiers were killed at or near Dunkirk, another six were taken prisoner, and one man died of his wounds in a German prison hospital.

After the Norway Campaign, the Boston Company of the 4th Lincolns did not see action again until the D-Day landings in Normandy in June 1944. The 4th Lincolns were not part of the first wave, and they cleared the beaches without loss of life. In fact, in the eleven months of the ensuing campaign across North West Europe their losses were relatively light. Just seven local men were killed, one of them being Major Jack Staniland. He was killed by his own men who, while on guard duty, mistook him for a German soldier.

Casualties on the Home Front were principally a result of German bombing raids. Between August 1940 and January 1943, the town suffered thirteen air raids. It is likely, however, that in some cases Boston was not the intended target and that the bombs that fell on the town were simply being jettisoned by the Luftwaffe before they made their escape back to Germany. But this was little comfort to their victims. The most deadly raid occurred on 12 June 1941, when a single bomb fell near James Street. It destroyed the Royal George pub and several houses and killed nine people, including an elderly man, two teenage girls and a mother and her three young children. A year later, in July 1942, a German bomber dropped four bombs aimed at the railway goods yard in High Street, but one fell short and killed an elderly lady and injured several others. About 100 people were also bombed out of their homes. Then just a month later, in August, four people were killed, five injured and another 150 bombed out when, during a night raid, four bombs exploded between Main Ridge, Silver Street and Threadneedle Street. Altogether, Hitler’s air force killed twenty Boston people and sixty-four homes were either destroyed or so badly damaged that they had to be demolished.

The news of Germany’s surrender in May 1945 was greeted with a mixture of relief and joy, although there were still many Boston men fighting the Japanese in Burma and the Far East. To celebrate VE Day, a large bonfire was lit on Bargate Green and, as a symbolic gesture, many of the wooden benches from the air-raid shelters were thrown on the flames. The May Fair was also held again for the first time since 1939 and became part of the celebrations. One local teenager many years later recalled that special day:

I remember Boston had an air of exuberancy that Tuesday. In the Market Place the steam yachts were operating outside the Scala New Theatre (now Marks & Spencer), amidst screams from the joyriders. The galloping horses outside Harlow’s butcher’s shop were ceaselessly turning round and round, up and down to the soulful sound of their organ music and people were queuing for rides on Lings Chaser … That night the Stump was floodlit. There were bonfires and dancing in the streets. Fireworks which had been purchased for the 1939 Guy Fawkes’ Night and been carefully stored were exploded instead of bombs.

The joy was marred, however, when a young soldier, 26-year-old Private Robert Freesland of the 1st Airborne Division, who had served in the Arnhem campaign, died in an accident at the fair. While standing on one of the rides he collided with another joyrider, was thrown off and died instantly.13

From Post-War Recovery to the Present

Boston’s economy recovered rapidly after 1945, and its development in the 1950s was far less dependent on the prosperity of local agriculture than it had been before the war. Industrial development was now more diverse. The printing, chemical and timber businesses all expanded markedly after 1950, and during the 1950s and 1960s there were also major developments in deep freezing, metalworking, engineering and fabrics. By 1960, two distinct areas of the town had developed as the town’s industrial zones. One was the dock itself, with its extensive timber storage areas, workshops and granaries, plus the area immediately to the north of the dock, on either side of the Skirbeck Road. The other was a new municipal trading estate off Norfolk Street, in an area where a few of the town’s larger employers, including Fisher Clark and United Canneries, had long been established.14

Relatively high levels of female employment, especially in the canning and feather factories, helped maintain family incomes in the 1950s and 1960s. E. Fogarty & Co., which from 1950 was under the control of the very energetic Charles William (Bert) Fleet, a former West Street butcher, grew rapidly, and quickly became one of the largest bedding manufacturers in the country and the largest employer in Boston. The adoption of man-made fibres was crucial to its success. During the 1950s the firm took over the other feather factories in the town and also acquired a factory at Billingborough. Until the rapid progress of quick-freezing in the 1960s, the canning factories also prospered, and the success of Fisher, Clark & Co. in printing self-adhesive labels ensured its expansion in the 1950s. Between 1957 and 1960 it needed to build a second factory on Horncastle Road. In 1960 the firm was bought out by a larger printing firm, Norcross, and it ceased to be a Boston family firm, but it continued to prosper within the larger organisation and, in 1968, was part of a merger that led to the creation of the very large print firm, Norprint. One of the town’s other long-established firms, Fogarty’s, also lost its independence, in 1987, when it became part of Coloroll.15

The town remained one of Britain’s smaller ports and in 1973 it was reported to be fortieth in the league table of ports as judged by the tonnage handled, but it was described then as being ‘in a thriving state’ with a ‘bright future’. In the late 1960s and early 1970s its trade was increasing almost every year. Deep-sea trawling was never re-established but the shellfish trade remained important. In 1971, 3,900 tons of shellfish were landed at the port. The trade of the port was also becoming increasingly diverse in the 1950s and 1960s, a trend that had begun before the Second World War. In the 1920s, Boston had been a trawling and coal-exporting port, but by the 1960s it was essentially an importer of West European produce, especially timber, foodstuffs and fertiliser. The relative importance of the coastal trade had also continued to decline as the port’s international trade increased.16

Boston’s population grew only slowly in the 1950s, but with higher housing standards now being demanded, housing estates continued to spread out from the centre into the open fields that surrounded the town, as they had begun to do before the war. Between 1951 and 1961, the population only grew from 24,453 to 24,915, but the pace quickened a little in the 1960s, and by 1971 the population had reached 26,025. The growth of the town’s built-up area between the wars had led to a change in the borders of the borough in 1932, with Skirbeck Quarter and part of Skirbeck village being added to Boston, and in 1974 the borough’s borders were again expanded. As part of the reorganisation of local government in that year, the borough of Boston was merged with the Boston Rural District Council to create a new, much larger entity, and the old Holland county administration disappeared.

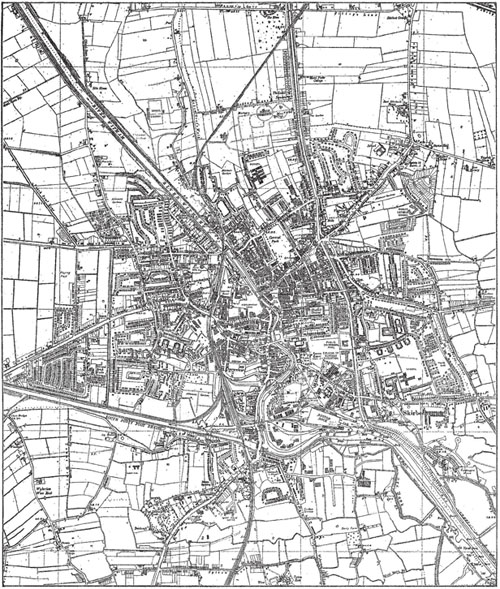

The steady growth of the town in the first two decades after the war can be seen in the following map of the town, drawn in 1972. This fails to show some of the most recent developments of the early 1970s, such as the building of the new Pilgrim Hospital just to the north of Burton Corner on the Sibsey Road (the A16), but the way in which new housing had continued to creep in all directions is apparent. By the late 1960s, low-density housing had filled all the area east of the Maud Foster Drain right up to the borough boundary, and some ribbon development had also extended eastwards beyond the boundary, along Eastwood Road. On the west side of the town, moreover, new housing had long been extending ever further westwards, and by about 1970, rows of suburban houses filled the former fields between the Sleaford Road and the South Forty Foot Drain to the west of the Cut Drain. Similar development had also occurred on the northern edges of the town, and along the London Road ribbon development now extended southwards towards the Frampton parish boundary. To the south-east, just south of the river, a new industrial area was beginning to develop around Marsh Lane.

Map of Boston, 1972.

The map also shows – if one has a magnifying glass – some of the future developments already planned for the town and in process of construction at the time the map was produced. Just across the river from the parish church, the slums of the Lincoln Lane area, north of West Street, had finally been swept away. The area is shown as a blank, stretching over about 10 acres, and described simply as ‘Development Area’. The new footbridge across the river, linking the area to Church Close and the east side, might also just be spotted. Planning for this redevelopment had begun in 1968, and the Lincoln Lane Development area was by 1972 already beginning to be filled up with new buildings and new streets. The first new public building here would be the District Police Headquarters, completed in 1974. In the following year, the Department of Health & Social Security offices opened, together with a new supermarket, one of the first in the town. A new bus station and car park completed the work.

The 1960s and 1970s was a time of radical change in the facilities and appearance of the town. Just as the Lincoln Lane redevelopment programme was getting underway, work had already begun on the new Pilgrim Hospital. A competition to design the new hospital was won in 1961 by the Building Design Partnership, but the need to provide more accommodation than had been at first planned meant that the final hospital – a series of single-storey buildings surrounding a ten-storey ward block – was quite different from the original plans. The first phase of building began in 1967 and was completed in 1970, and phase two was completed in 1974. A third phase was begun in 1985 and completed in 1987.17

The Pilgrim Hospital.

The 1960s also saw the disappearance of many of the Georgian warehouses which lined the old harbour and which had once played such an important role in the life of the town. The so-called ‘London Warehouse’, built by the corporation on Packhouse Quay in 1817 and long used as a bonded warehouse by Ridlington’s wine merchants, had been demolished in 1948, and a group of riverside buildings on the opposite bank went at about the same time. Most of the other warehouses survived, however, until the 1960s. Ships no longer came up to either the Packhouse Quay or the Doughty Quay, but many of the former granaries and other warehouses had found alternative uses. Then, in the mid-1960s, a number of old buildings were demolished to either make way for a new bridge over the Haven or to widen South Street and the other roads leading to the bridge. Among the warehouses to disappear at this time were the Carlton Works, also known as Sheath’s Granary, which dated from the mid-eighteenth century and was last used by W.W. Johnson & Sons, the seed merchants; Gee’s Granary, which dated from the late eighteenth century and stood on the opposite bank, in High Street, just to the south of Doughty Quay; Waite’s Granary, just to the north of Packhouse Quay, dating probably from the beginning of the nineteenth century and used up until 1963 by W. Sinclair & Son as a seed and oil store; and the St Anne’s Lane warehouse, also built during the nineteenth century. Other buildings demolished to make way for the new bridge included a couple of pubs on the High Street; the Lord Nelson and the Royal Oak.18

The widening of South Street and the building of the new Haven Bridge was completed in 1966 and helped speed the ever-increasing flow of traffic that was now coming into the town every day. During the 1970s, however, a more drastic solution was adopted when a new dual-carriage road, the John Adams Way, was cut through the town from the northern end of Wide Bargate to the new bridge, where it joined a new and equally wide Spalding Road, running southwards between the old London Road and the railway line. The route chosen for the John Adams Way was highly controversial; partly because it cut a swathe through the old town, very close to the town centre, but also because it effectively cut the eastern side of the town in half. Moreover, in the years that followed it would be found that the new road had not solved the town’s traffic problems, and as they increased, and other towns gained bypasses in the 1980s and 1990s, so a campaign for a bypass for the town would also grow.

Among other familiar consequences of the growing popularity of the motor car was an increasing proportion of the town’s workforce choosing to live outside the town and to commute into work. A survey made in 1971 revealed that almost 40 per cent of those working in Boston commuted from nearby villages or other towns. This was one of the highest figures for any town in the county. Some commuters cycled or came in by bus, but an increasing proportion came in by car. Those choosing to live out of the town in the post-war years tended to be the higher earners. A survey of 1966 found that in the rural areas of Holland, 11 per cent of households already had more than one car, compared with only 6.5 per cent of households in Boston and Spalding, and the numbers of households with no car at all was also greater in the two towns than in the surrounding countryside: 53 per cent compared with 37 per cent.19

Another consequence was the ‘Beeching Axe’: the proposals made in the early 1960s by Dr Beeching for a drastic reduction in the number of railway lines in the country, and particularly in rural areas such as Lincolnshire. By this time the increase in road haulage had considerably reduced the amount of freight carried on the railways in east Lincolnshire and it was this, as well as a fall in passenger traffic, which led to the closure of the ‘Loop Line’ from Boston to Lincoln in 1963 and to the Peterborough-Boston line being included in a list of proposed future closures. Vigorous opposition delayed the fall of the axe for seven years, but the last London-Grimsby train via Boston ran on Sunday 4 October 1970. From now on the town’s only railway lines were those to Skegness and Grantham due to the preservation of the Nottingham-Grantham-Boston-Skegness line, partly because of the considerable Skegness holiday traffic in the summer months. This meant that Boston retained its link with London, but only by travelling first to Grantham. This was a much slower journey than the previous direct line to Peterborough.20

From the 1970s, cars rather than sheep, pigs or cattle filled the ancient market area of Wide Bargate, and the closure of the town’s canning factories in the 1970s and 1980s marked a further reduction in the town’s links with its agricultural hinterland. More warehouses beside the river also closed in the 1970s and 1980s, including the Lincoln warehouse in South Street, which was converted into the Sam Newsom Music Centre in 1978, named after the last Chief Education Officer of Holland County Council. Harrison & Lewin timber yard at the end of Custom House Lane closed down at about the same time, and the Custom House itself, on Packhouse Quay, closed in the 1980s. By 1993, almost every warehouse and commercial building on Packhouse Quay had gone and the South Street area had long lost its former commercial importance, instead becoming a cultural quarter. Across the road from the Music Centre stood the Guildhall Museum and the Pilgrim College Adult Education Centre, housed in Fydell House. Just around the corner, down Spain Lane, the former Dominican friary building had been converted some years earlier into the Blackfriars’ Art Centre, the first purpose-built theatre constructed in the town for over 100 years. The proposal to adapt the old building and build a theatre in the yard between the friary infirmary and the Guildhall had been first made in 1961 by Alan Blakeley, the deputy headmaster of St Nicholas’ School, and the theatre had opened five years later.21

A former warehouse which is now the Sam Newsom Music Centre.

Boston had been slow to appreciate its heritage, apart from the Stump, but the formation of the Boston Preservation Trust in 1935 and its purchase of Fydell House was an important first step. Another valuable initiative was the History of Boston Project of the 1970s, which did excellent work in raising public awareness and knowledge of the town’s history by producing a series of well-researched and well-written booklets on different aspects of the town’s past which many, including this author, have found invaluable. But as we have seen, the 1960s and 1970s also witnessed the loss of much of the town’s Georgian and pre-Georgian heritage, including the Peacock & Royal Hotel and numerous historic warehouses. Steps to preserve the town’s last windmill, the Maud Foster Mill, built by Isaac and Thomas Reckitt in 1819 (and until 2012 the highest surviving working windmill in the country), were only taken in the 1980s and early 1990s, when it was restored and converted into a museum. Those warehouses that survived into the new millennium have mainly been converted into flats and the long-neglected Hussey Tower, although still the property of the borough council, has since 1996 been the subject of a local management agreement which ensures that it will be maintained in good repair by the Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire. More recently, that same organisation also helped raise over £2 million to rescue a fine mid-eighteenth century house at No. 116 High Street, the former home of the Garfit family, where William Garfit had opened the first bank in Lincolnshire in 1754. Although a Grade II listed building, it was by 2010 in a most dilapidated state and in imminent danger of collapse.

The former medieval guildhall, now the Guildhall Story Museum.

Fydell House, built around 1700 for the Jackson family and sold to Joseph Fydell in 1726. It is now known as the Fydell House Centre, a venue for weddings and receptions, evening and day classes, recitals and garden parties.

The former Dominican friary infirmary, now the Blackfriars’ Art Centre.

No. 116 High Street today, recently restored by the Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire. This fine house has been a bank, a family home and a ‘Home for Fallen Women’.

Warehouses have since become flats on South Square. In the middle, Hurst’s warehouse has become Haven Hall and John Watson’s warehouse, to the left, has become Riverside Lodge. Both were built around 1810. Hurst’s warehouse was built by Thomas Fydell when he demolished the thirteenth-century Gysor’s Hall, which stood on this site. Stones from the medieval house can be seen incorporated in the wall of the ground floor.

The Maud Foster windmill.

Two new secondary schools that had been planned before the Second World War, Kitwood Boys’ School and Kitwood Girls’ School, finally opened once the war was over, named after Alderman Tom Kitwood, the former chairman of the County Education Committee who had championed the original plans ten years earlier. At first, however, the staff and pupils had to make do with temporary accommodation and the new buildings were not completed until the 1950s: the boys’ school on Mill Road, in Skirbeck, and the girls’ school on Marian Road, on the north side of the town. The new schools were secondary moderns, taking those pupils who did not pass the eleven plus examination. Together with the Boys’ Grammar School and the Girls’ High School they catered for all secondary-aged pupils in the town and in the northern half of Holland. The town’s other schools became primary schools but in the 1960s and 1970s a number of new primary schools were built to replace them, and by the 1980s almost all of the town’s Victorian elementary school buildings had been closed.

Between 1962 and 1964 the Holland County Council (which since 1945 had had responsibility for all state education in the town) built a large College of Further Education on Rowley Road, near the Boys’ Grammar School. This was effectively the successor to the old Boston Science and Art Class which had been founded in 1861 and which had occupied rooms in the Municipal Buildings since 1904. The art department of the new college took over the building previously used as the British (or Public) School, but had to move again in the 1970s when the old building had to be demolished as it lay in the path of the new John Adams Way.22

The town’s sports clubs have had a somewhat chequered history in recent years. One new development in the 1970s was the introduction of speedway racing at a stadium in New Hammond Beck Road, and for a few years the sport enjoyed great success in the town. The Boston Barracudas raced in the British League Division Two and in 1973 not only topped the league but also won the Speedway Knockout Cup, while a member of the club, Arthur Price, won the League Individual Championship. However, in 1988 the stadium was sold for redevelopment and no alternative could be found. In the 1990s, the local team, racing in the Conference League and known simply as Boston, had to make King’s Lynn their base.

The long-established Boston Rowing Club has enjoyed more lasting success. The highlight of the club’s year is the annual 31-mile Boston Rowing Marathon from Lincoln to Boston, which is held every September and attracts competitors from all over the country. Swimming has also flourished in the post-war era and the town is now home to a successful swimming club, the Boston Amateurs. The club hosts two club championship events and many galas and other competitions, including the Boston Open. The members train at the Geoff Moulder Leisure Complex, next to Boston College, on Rowley Road.23

A new stadium, the Princess Royal Sports Arena, which opened in October 2003 on the Broadsides, to the west of the town, has been an important addition to the sporting and social life of the town. The stadium is particularly noted for the careful planning undertaken to ensure that disabled athletes and spectators can enjoy full access to all its facilities. It has a pool, gym, indoor and outdoor athletics tracks, badminton courts and a 5-a-side football pitch. It has also become the home of the Boston Rugby Club.24

One feature of Boston’s recent sporting history, however, has been less encouraging. In 2002, after many years as a non-league club, the town’s principal football team, Boston United (or the Pilgrims) finally won promotion to the Football League. However, the fans’ joy at this success was quickly dented when, in its first year in the League, the club was fined by the Football Association and had points deducted for breaching rules regarding registration of players. But much worse was to come. In 2007 the team was relegated on the last day of the season, and then suffered the disgrace of having the manager and former chairman plead guilty to ‘conspiring to cheat the public revenue between 1997 and 2002’. The club had also acquired enormous debts and this put it into administration, triggering further FA punishment, and a further demotion. During the 2010/11 season the team was playing in the northern section of the Second Division of the Blue Square Conference. A second team, Boston Town (or the Poachers), plays in the United Counties Football League. Boston United’s ground is still in the town centre, on York Road, with a capacity of about 6,200. Boston Town play on Tattershall Road, on the northern edge of the town.25

The Princess Royal Sports Arena, opened 2003.

The sad story of the town’s football club was played out against a background of growing concern in many quarters, regarding many aspects of the town’s development as it entered the new millennium. Growing public concern regarding immigration, crime, anti-social behaviour, drug and alcohol misuse, traffic problems, litter, pockets of deprivation, and the physical health of the community have been well-publicised in the national press. In 2006, local health problems were highlighted when a national newspaper claimed that Boston had the highest per capita number of obese people in the country, with one in three adults said to be clinically obese. Figures for 2010–11 seemed to show that the situation had improved but Boston’s adult and child obesity levels were both still above the national average, as were the numbers of diabetes sufferers (a problem often associated with obesity). There was little doubt that many families’ dietary habits were far from healthy and, with obesity problems in mind, those designing the Lincolnshire Local Area Health Agreement for 2011 chose to make the encouragement of more physical activity for both children and adults one of its top priorities. Death rates in Boston in 2010 were also above the national average and, closely related to this, the number of adults who smoked was also very high; one of the highest in the country. Equally depressing – rates of teenage pregnancy were above the average for the country, as were levels of drug misuse.26

Many of these problems are associated with deprivation and poverty. In its Annual Report for 2010–11, the local council noted that although the borough was by no means one of the country’s most deprived areas, and ranked 109th out of 354 towns in the country, the area had ‘become relatively more deprived in recent years’. Unemployment levels, however, were very similar to those in South Holland and East Lindsey, and lower than those in Lincoln. In May 2012, 3.8 per cent of 16–64 year olds in the area were claiming Jobseekers’ Allowance (compared to 5.3% in Lincoln). The more serious long-term problem, as the council recognised, was ‘the considerably lower earnings and skill levels’ of the area’s workforce.27

Areas of deprivation, both in the town and in the surrounding countryside, may also help explain some of the problems faced by local secondary schools, particularly relatively low GCSE scores, compared to those of other schools in the county. There can be little doubt, however, that the facilities and curricula choice available to the pupils had improved considerably between 1992 and 2012. In 1992 the Kitwood Boys’ and Girls’ schools merged to form the Haven High Technology College, based in the former girls’ school on Marian Road, although the boys’ school did not finally close until a year later. Today, Haven High is part of a 3–16 school federation, and in 2012 had approximately 1,200 students on two sites. In 2011 it absorbed the pupils of the St Bede’s Catholic Science College, the town’s other all-ability secondary school, which closed in that year. The federation also includes the Carlton Road Primary School and Staniland County Primary. New facilities which have been installed at the college in recent years had enabled it to expand courses in motor vehicles and to add new courses in construction and salon services. Plans to merge the Boys’ Grammar School with the Girls’ High School to form a federal structure were well advanced in 2008–09 when the scheme was abandoned. The former Kitwood Boys’ School became the De Montfort campus for the new Boston College in 2003, while the former College of Further Education became the college’s Rochford campus.28

The Haven High Technology College.

The failure of the local council to obtain a bypass for Boston, in spite of regular gridlocks on the John Adams Way and the Sleaford and Spalding roads, led to increasing frustration in the town and prompted the formation of a number of bypass pressure groups. It was still a surprise to many, however, when the Boston Bypass Independents campaign group stood for election in all thirty-two seats of the borough council in 2007 and won twenty-five seats. This gave it control of the council, and it was the first group or party to do this since the new borough of Boston was created in 1974. This was also, however, almost certainly a reflection of a wide range of discontents and concerns. The new leader of the council, Richard Austin, described the result as ‘a reflection of the black mood of the people of Boston’. Unfortunately for the cause, however, the group quickly split in two, and then in 2011 was almost wiped out altogether when the Conservatives won nineteen seats and took control of the council. At the time of writing, Boston still has no bypass but it is a high priority for Lincolnshire County Council – which is also the highways authority – and if regional funding is made available by central government, the town might hope for a bypass to be built in the next ten or fifteen years.29

Boston is changing rapidly, and perhaps the greatest challenge facing the town today – and one reason for the discontent shown in 2007 – is the social tension and ill-feeling which has accompanied the settlement of large numbers of migrants in the town and the surrounding area since the beginning of the new millennium. Following the decision of the European Union to allow free movement of labour between member countries, Boston has experienced a considerable influx of European immigrants, especially from Portugal and, more recently, from Poland and the Baltic states. This has played a major role in increasing the population of the borough by almost 9,000 in the last ten years, from 55,750 in 2001 to 64,600 by 2011. This increase – 15.9 per cent – is the highest in the country and twice the national figure (7.8 per cent), which is itself a record.30

Articles in the national press about European migration to Boston in recent years may have exaggerated some of the problems created, but one result has been a decline in the level of social cohesion. A survey conducted by the council between 2008 and 2009 found that 45 per cent of respondents felt that people from different backgrounds did not get on well together, and the same proportion also felt that people in the town did not treat each other with sufficient respect or consideration. Two violent incidents, in 2004 and 2006, when local youths attacked shops and bars belonging to immigrants before the police were able to intervene, certainly helped create an unfortunate image for the town and exacerbated social tensions. However, since 2006 the situation has improved somewhat and many local people, especially employers, have voiced their admiration for the strong work ethic and skills of many of those who have come from other countries in recent years to make their homes in Boston. A second survey, conducted in 2010–11, showed at least a little improvement in people’s perceptions of how well people from different backgrounds got on together. The number who judged relations to be poor had fallen to 39 per cent, but only 14 per cent rated Boston as a ‘good place’ for inter-community relations. At the end of 2011 a march through the town in protest against immigration was only cancelled when the council promised to investigate the issue thoroughly. There is no doubt that the size and rapidity of immigration has created many problems: pressure on doctors’ surgeries has increased and the local schools struggle to meet the demands of large numbers of children for whom English is their second language, and whose parents speak little or no English. In March 2009, Haven High School reported that 17 per cent of the pupils on its roll were foreign nationals, mainly from Poland and Lithuania. In a local by-election the BNP won a seat on the borough council in 2008 but lost it again in 2011.31

Boston, like other East Coast towns, also faces the problem of flooding. In 2010 a survey found that 88.7 per cent of houses were at risk of flooding. As part of the Town Regeneration Scheme plans have been drawn up to build a tidal barrier on the Haven to protect the town’s homes and businesses from a tidal surge. It is intended that work on this will begin in 2016. It is anticipated, however, that this flood defence measure will also be a major boost to the town’s economy. If the barrier can also be used to raise the level of water in The Haven, the town’s future as a centre for pleasure craft – with a greatly expanded marina – could also be secured, with highly significant financial implications for the town. Once again, as throughout its long history, the state of the Haven and the prosperity of the town remain inextricably linked.32