two

THE LATE MEDIEVAL

TOWN,

1300–1500

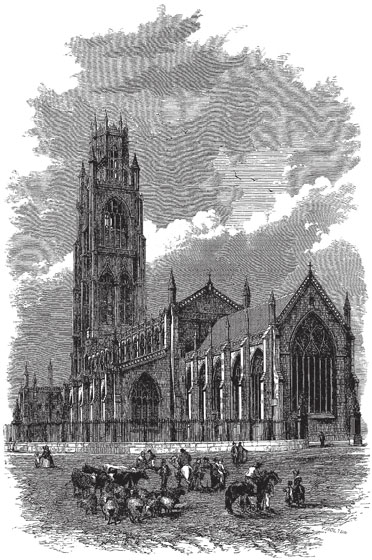

The Rebuilding of St Botolph’s

The great church of St Botolph, affectionately known as ‘the Stump’, is striking testimony to the wealth and confidence of the town in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. When completed, it was 282ft high and more than 20,000 sq. ft in area, about seven times as large as its Norman predecessor. It has been described by Pevsner and Harris as ‘a giant among English parish churches’. It is now believed that it was probably begun in the 1330s or 1340s, when the area of the graveyard was considerably expanded, and not, as traditionally believed, in 1309. The tower was not begun until the late fourteenth century and it was only completed between 1510 and 1520. The 1309 foundation date comes from the eighteenth-century historian, Dr William Stukeley, who stated that the first stone of the foundations of the tower were laid by Dame Margery Tilney in this year, ‘on the Munday after Palm Sunday’. The tower, however, is built in the Perpendicular style and was clearly built after the rest of the church had been completed, mainly in the fifteenth century. Moreover, the document from which Stukeley quotes has long since disappeared. Ever since Stukeley published his findings it has been assumed that the nave and chancel were begun in 1309, or shortly afterwards, but both the architectural evidence and surviving fourteenth-century records tend to support a start date either in the 1330s or 1340s.1

The Tudor antiquarian John Leland also tells us that the first stone of the tower of the new church was laid by one ‘Dame Mawde Tilney’, but the lady referred to by Leland is most likely to have been Margaret, the wife of Frederick Tilney, who was alive in the last decades of the fourteenth century, and not the Dame Margery of the first decade of the century, identified by Stukeley as the founder. The Tilneys were generous benefactors of both the church and the guilds, and the story that she laid the foundation stone of the tower is entirely credible. The date of the tower’s foundation was probably 1389, however, and not 1309, as Stukeley suggests. Dame Margaret was also credited with having contributed £5 towards the initial costs of the foundations and similar sums were said to have been given for this purpose by the vicar, Sir John Truesdale, and by one of the town’s merchants, Richard Stevenson. Truesdale’s name was probably added to the story later, for he had been the vicar at the beginning of the fourteenth century, but the records of the Guild of St Peter and St Paul show that there was a Boston merchant called Richard Stevenson active in the 1380s.

The chancel and the nave were both built in the Decorated style using stone brought from the quarries at Barnack, near Stamford, presumably transported mainly by water. The south side of the nave, at least, must have been completed in the early 1350s, as the chapel of the Guild of Corpus Christi, built on the south side of the church, was already in use by 1354. The work then continued into the 1360s, when indulgences were offered to those who gave money for ‘the repair of the church and chancel of St Botulph …’ This reference to the church, in the Calendar of Papal Registers, also suggests that the church and chancel were being built at the same time, and not proceeding from east to west, as has often been assumed. The work appears to have been completed by about 1370 but then, early in the fifteenth century, the windows of the two most easterly bays of the chancel, on both the north and south sides, were apparently taken out and replaced with the latest Perpendicular designs. This may have been done to give the chancel a more ‘up-to-date’ look and perhaps allow for the use of new glass designs. The frames and mouldings of these windows are identical to those of the more westerly bays, which suggests that they were built at much the same time, and that there was no later lengthening of the chancel, as was once thought to be the case. It is now also thought that the sixty-two carved misericords which form part of the chancel seating were probably also completed in the first two decades of the fifteenth century, at the same time that the new windows were installed. From about 1381, there had been at least fifty-seven clergy attached to St Botolph’s. It is likely that the changes made to the chancel in the early fifteenth century were designed to reflect the church’s increasing status.2

Fourteenth-Century Prosperity

The decision to undertake the building of a much larger and more prestigious church in the 1330s or 1340s was a reflection of the wealth, size and importance of the town by this time. Its merchants were among the richest in the country, as was made clear in 1332 when a tax on moveable wealth was imposed. It was found that there were more wealthy people living in Boston than in any other Lincolnshire town. The town’s average taxpayer paid 9s 3¾d. This meant that Boston was by far the most prosperous community in Lincolnshire, and the fourth wealthiest provincial town in the country. Its total valuation in 1332 was put at £914, almost ten times that of Grimsby (whose tax-paying population was only a little smaller), and almost equal to that of Lincoln, whose tax-paying population was three times as large. Eleven Boston men were taxed on £15 or more worth of moveable items, and one man, John de Tumby, was judged to have £70 worth of ‘moveables’. The town’s two richest men, assessed at £70 and £30, were together taxed on more wealth than all of Grimsby’s seventy-nine taxpayers put together.3

Although at this date foreign merchants were still predominant in international trade, Boston merchants such as John de Tumby were now heavily involved in the wool, wine and cloth trades, as well as the export of salt, for which Boston was the chief port, and the very considerable coastal and international trade in wax, lead and foodstuffs. The de Tumby family had been prominent members of the town’s merchant community for many years. In 1260, Walter de Tumby had been one of the founding members of the Guild of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Boston’s oldest guild, and in 1308–9 and 1311, a John de Tumby was listed as one of the English wool exporters operating out of Boston. English merchants were now playing an increasingly important role in the wool export trade, and members of the de Tumby family were among the frontrunners. At least ten Boston merchants were exporting wool from the port between 1308 and 1311, four of whom (including de Tumby) could be judged as being among the country’s wealthiest wool merchants. Nearly a thousand sacks (or nearly 200,000 fleeces) were exported by Boston merchants in the twenty-nine months covered by the accounts, and more than a quarter of these were accounted for by de Tumby alone.4

Wealth from wool: St Botolph’s church from the southeast, as it appeared around 1850. (Drawn by J. S. Prout)

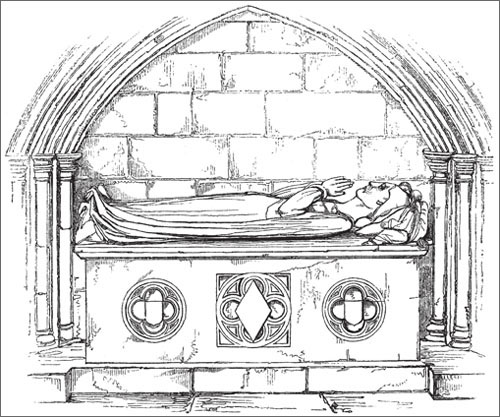

Altar tomb of a lady (c. 1450–60), in the south aisle of St Botolph’s church. Tradition has ascribed this effigy to Dame Margery Tilney, who was said to have laid the foundation stone of the new church in 1309. The tomb commemorates a lady of the mid-fifteenth century, however, who was probably the wife of the unknown knight whose effigy stands nearby. When the tomb was restored in 1850 the Tilney arms were placed on it. The effigy is carved in alabaster. Puppies at her feet nibble at her dress.

Although it was now second to London as a wool-exporting port, during the first decade of the fourteenth century wool exports through Boston remained as high as in the 1280s and 1290s. It also remained an extremely important port for the import of wine and cloth (again, second only to London). During the next two decades, however, overseas trade suffered a sharp decline and the wealth of the town, as revealed by the tax assessments in the 1330s, would have been even greater but for this. Moreover, throughout much of the first half of the century, the volume of both exports and imports at Boston fell. Wool exports were badly damaged by the renewal of warfare with France, by the outbreak of civil war in Flanders, and by the declining fortunes of the town’s fair. In 1334 it was reported that the profits from the fair barely exceeded £100 – less than half the figure recorded in the 1280s – and the reason given was that ‘foreigners come not as they were wont to do’. Ironically, it would seem that just as a beginning was being made to the building of an impressive and much larger church, the trade of the town was facing the first serious checks to its prosperity.5

Altar tomb of a knight (c. 1450–60), in the south aisle of St Botolph’s church. His identity is not known, but he appears to be a member of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, which had built a church and hospital dedicated to St John at the southern end of the town in the thirteenth century. According to local tradition, the tomb was brought from that church when it was demolished in 1626. The knight wears the cross of his order on a chain around his neck. Like the monument to a lady, the effigy is carved in alabaster. The knight may have been a member of the Weston family, which included prominent hospitallers in the fifteenth century.

All over Europe the great international fairs were in decline in the fourteenth century, as wholesale trade came to be more centred on major towns rather than on fairs. The fair at Boston, however, was also badly affected by a sharp decline in the number of Italian merchants choosing to export wool from east-coast ports early in the century. In 1317–18, for instance, the Bardi house exported over 500 sacks from Southampton but a mere forty-one through Boston. Piracy and maritime warfare now encouraged Italian merchants to seek the shortest possible cross-channel sea route, and while London and the south-coast ports benefitted, the trade of Boston and other east-coast ports suffered decline.

To some extent the reduced importance of the Italians created new opportunities for Boston’s own merchants, as the figures quoted previously for 1308–11 have indicated, but Boston merchants, it would seem, proved less successful than those of Hull in exploiting such opportunities. During the 1320s the quantities of wool exported by Flemish and Hanseatic merchants from both ports also declined but Boston’s merchants were less successful than those of Hull in recouping this loss by expanding their own trade. Boston remained England’s second wool port throughout the 1320s but was overtaken by Hull in the 1330s, and its share of the total wool trade declined from 26 per cent between 1304 and 1311 to 21 per cent between 1329 and 1336. Moreover, Boston’s wool trade was at this stage still heavily reliant on foreign merchants, and particularly on the Hansards. Between 1329 and 1336 they still accounted for more than half the wool sacks exported from the port; at Hull, by contrast, the trade in foreign hands was only a sixth of the total, and in London it was little more than a third.

Cloth exports also fell sharply in the 1320s and 1330s, and the fall in exports through Boston was not compensated for by any growth in imports. The duties paid by foreign merchants on cloth imports from Flanders show that this trade was also badly affected by warfare and internal social conflict. The quantity of wine imported by foreign merchants was also in decline in the 1330s and then plummeted following the outbreak of the Hundred Years’ War in 1337. The outbreak of the Black Death in 1348–9 brought further disruption. For five years, from 1348 to 1353, no imports of wine by foreign merchants are recorded at all.6

Following the Black Death, however, and throughout the second half of the century, the overseas trade of the port grew once more, and Boston continued to enjoy considerable prosperity. How many were killed when the Black Death reached Lincolnshire in 1349 is not known, but the prosperity of the town in the second half of the century would suggest that its population was soon growing again. By the time of the Poll Tax of 1377 there were 2,781 taxpayers, male and female, over the age of 14. This probably represented a total population of about 5,500, making it the tenth largest town in the country.7

Incised slab of Tournai marble depicting Wisselus de Smalenburgh of Munster, a Hanseatic merchant, who died in Boston in 1340. His monument is at the east end of the north aisle of St Botolph’s. He was buried in the church of the Greyfriars and the monument was excavated from that site in the early nineteenth century. In 1897, it was transferred to St Botolph’s for its better preservation.

When the Lincoln staple was set up in 1353, Boston was specified as the port for exporting wool and all other goods taxed at Lincoln, and in 1369 the staple itself was transferred to Boston. This probably followed vigorous lobbying by its merchants, and it was held in spite of petitions from Lincoln, Nottingham, Derby and Leicester. In 1377, when the king granted a monopoly of wool exports at Boston as part of a repayment of a royal loan, twenty-two merchants from Boston were listed as being able to benefit, along with ten from Lincoln. Government policy to give English merchants a monopoly of wool exports reduced the total quantity of wool exported from Boston in the late fourteenth century but the quantities exported by English merchants, including those of Boston, remained buoyant until the end of the century. Of the 210 English merchants who received pardons in 1395 for frauds in buying and selling wool, nineteen were from Boston.8

The town’s prosperity in the second half of the century was also boosted considerably by the growth of exports of English cloth, and especially cloth made in Coventry, which was now emerging as one of the country’s leading cloth-producers. The customs statistics show only negligible exports in the mid-1350s, but by the end of the decade about 900 cloths were being exported annually, and by the end of the century over 3,000 were being exported every year. About two thirds of the trade was in the hands of the Hanseatic merchants, who either shipped the cloth directly to Bergen, from which they imported stockfish into Boston, or as part of a triangular trade, taking English cloth to the Baltic ports, and then grain from the Baltic to Bergen, before importing Norwegian stockfish to Boston. During the 1380s and 1390s, English merchants were shipping abroad about 800 cloths every year through Boston, mainly to ports in the Baltic, and especially to Danzig and Stralsund.9

By the 1390s, however, wool and cloth were the only goods still being exported in large quantities through Boston. Salt exports had ended, as local salt makers had found that they could not compete with foreign imports; exports of cereals and other foodstuffs – which had been quite important at the beginning of the century – had also virtually ceased, and other exports, such as Derbyshire lead, Nottingham alabaster ware, calfskins, rope, blankets and canvas, were now shipped from Boston only in small quantities.

The seal of the Boston staple, used by the mayor of the staple to stamp all goods weighed at the Boston Custom House in the steelyard.

Apart from wool and cloth exports, another thriving aspect of the town’s trade in the 1390s was the import of various commodities from Scandinavia, the Baltic and the Low Countries. As well as stockfish, Hanseatic merchants were also importing into Boston considerable quantities of oil, furs and timber. The value of the import trade at Boston in the hands of foreign merchants grew markedly in the second half of the century, reaching a peak of about £9,000 per year between 1377 and 1387, and then averaging about £6,000 per year during the next twenty years. At the same time, English merchants operating through Boston were importing large quantities of dyestuffs for the expanding native cloth industry, mainly from the Low Countries, which acted as an entrepôt for goods from southern Europe and the Near East. English merchants were also sailing into the Baltic to buy iron from Danzig, copper from Sweden, Prussian canvas, rye, and forest products such as timber, pitch and bitumen. English merchants also controlled wine imports by the second half of the century, and about 330 tuns of wine – mainly from Gascony – were being imported every year in the 1390s, but this was far less than the quantities being imported by foreign merchants in the 1320s.10

Some of the town’s merchants were among the wealthiest and most important men of the county in the late fourteenth century. One such man was the wool merchant Frederick Tilney, a member of an old Boston family whose members had included benefactors of the church and friaries. The family also provided the county with sheriffs and MPs, and gave their name to Tilney Lane in Boston. He was admitted to the Guild of Corpus Christi in 1349 and by 1356 he was thought sufficiently prominent in the wool trade to be summoned to Westminster to discuss royal policy on the trade. The absence of customs accounts for the later years of Edward III’s reign means that little is known about his business activities, but in 1377 he was one of the twenty-two Boston merchants licensed to export wool. When Tilney died in May 1378, he had served as a customs collector for twenty-seven years, had been the town’s first mayor of the staple, and had also served as a royal commissioner of dykes and ditches and a commissioner of the peace. He and his wife were also prominent members and benefactors of the Guild of the Blessed Virgin Mary, as well as the Guild of Corpus Christi, and at the time of his death he owned property in Pinchbeck, Holbeach, Skirbeck, Freiston, Leake and Leverton, as well as further afield, in north-west Lincolnshire. We have seen that it was probably Margaret, his widow, who laid the foundation stone for the tower of the new St Botolph’s, about ten years after his death.

Another powerful and very wealthy townsman and wool merchant of this period was William Spaigne. He too was a member of an old Boston family, whose name is perpetuated today in Spain Lane, and in many respects his career was very similar to that of Frederick Tilney. Again, little is known of his business dealings except that he exported wool through Lynn and Boston, and was able to acquire land in Boston and nearby villages, such as Skirbeck, Wyberton and Holbeach. His role in county administration, however, was quite remarkable. Like Tilney, he was also summoned to Westminster in 1356 to give his advice on the wool trade. He also frequently served as a royal commissioner of dykes and ditches, commissioner of the peace and commissioner of labourers. Spaigne was also a commissioner of oyer and terminer (appointed by the Crown to hear and determine particular criminal cases). He was twice elected Sheriff of Lincoln (from 1378 to 1379 and 1384–85), served as an MP, elected to represent the county to the parliaments of 1380 and 1382; and was for many years a senior official of the Honour of Richmond, the estates of which included the greater part of the town. He is thought to have been Chaucer’s model for ‘The Franklin’s Tale’.

The seal of the Guild of Corpus Christi.

No other Boston merchant at this time played such an important role in county administration as Spaigne, but a member of the next generation of wealthy local merchants, John Belle, also held royal commissions to act in local administration, and, like Spaigne, was also an officer of the Honour of Richmond, appointed bailiff for Boston (the chief manorial official in the town) in 1380. In 1398 he was chosen to be a Justice of the Peace and in 1414 he was also chosen to represent the county in Parliament. We also know that he was very well educated, as perhaps were some of his fellow merchants, because in about 1400 he composed a long satirical poem in Latin attacking the corruption of Treasury clerks, based on his experiences of the harassment he had suffered at the Exchequer. A little is also known about his trading activities. In 1384 he was exporting cloth from Boston and between the years 1395 and 1398 he was one of the largest sellers of cloth in the county. He is also recorded as importing oil, wax, herrings, canvas and Spanish iron. He was an official of the Boston staple and probably also a wool exporter. In 1398 he was one of the Boston men commissioned to assemble ships to attack pirates.11

Belle was one of eleven Boston men who were judged in 1388 to be among the ‘gentlest and ablest’ men of the shire, who were required to swear an oath to support the so-called ‘Merciless Parliament’ in its dispute with Richard II. Another merchant also required to swear the oath was John Rochford, who was the richest of the town’s 1,600 taxpayers listed in the 1381 Poll Tax return, paying 8s. Like Belle, he was an officer of the Boston staple and probably a wool exporter. At least four other oath-takers were also wool merchants (John Harsik, James Skirbeck, Robert Norwode and John Holmeton), as probably was another merchant, Gregory Mille, who – like Belle and Rochford – was also an official of the staple.

Like Spaigne and Tilney before them, these Boston merchants, the elite of the town, were also landowners and senior members of the richest guilds in the town, those of Corpus Christi and the Blessed Virgin Mary. Most of their properties were to be found in the town or nearby, but some also held lands in other parts of Holland and even further afield, at Alford, Well, Healing and Great Cotes, near Grimsby. Nine of the Boston oath-takers are listed as members in the register of the Corpus Christi Guild. Less is known about the members of the Guild of St Mary, but at least three of the eleven were also members of this guild too, and at least one – John Belle – was a member of the Guild of St Peter and St Paul.

Two other late fourteenth-century Boston merchants worthy of mention were William Harecourt and Walter Pescod. Harecourt was mayor of the Boston staple in 1374, and in 1381 he, like Pescod, was one of the town’s top taxpayers, being one of five townsmen who paid 3s 4d. In 1383 he was charged with fraud and an inventory was made of his goods, which throws some light not only on the wealth and pastimes of William Harecourt, but probably also of some of the other wealthy merchants of the town at this time. The inventory included eight bowls bound with silver gilt, three lidded silver cups, six silver cups, six silver plates, numerous beds and their trappings, brassware, pewter and furniture, and, most interestingly, two hawks and a ‘gentle’ falcon, highly prized at £10. When not attending to business, we can imagine William and some of his fellow merchants and other friends hawking on the Lincolnshire Fens.

Walter Pescod has the distinction of being the only merchant from this period to have a fine monumental brass that has survived, although not entirely intact, in the parish church. He died in July 1398, when he was about 50, and was buried in the guild chapel of St Peter and St Paul, the guild to which he and his wife both belonged and of which they were major benefactors. He was a wool merchant and in 1395 he was one of the Boston merchants pardoned for fraud in purchasing and selling wool. He dealt, however, as did many of his fellow merchants, in a wide variety of goods. He imported herrings (£42 worth in 1393), iron, oil, and dyestuffs and alum (a mordant for fixing dyes) for the English cloth industry. In 1394 his mixed cargo of iron, oil and other goods was valued at £100, and a cargo of alum imported in 1387 at £20. We can be fairly sure that he travelled regularly to Coventry, where the clothiers were among his largest customers, because he and his wife were also members of the prestigious Holy Trinity Guild of that town. Membership of the guild would have been important in establishing vital friendly relations, not only with the leading families of the town and district but also much further afield, as the guild attracted members of the gentry and merchant classes from across the country, from Cumberland to Wiltshire. The building currently known as Pescod Hall that stands in Pescod Square was built in about 1450, replacing the earlier family home and business centre that Walter Pescod would have known.

Some of the most powerful men in the town in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century, however, were not Boston men at all, but wealthy merchants of other towns who shipped goods through the port and held positions of responsibility for the administration of the trade. Two such figures were the Sutton brothers, John and Robert, both of whom were extremely wealthy Lincoln merchants who traded through Boston in the late fourteenth century, exporting wool and cloth and importing mainly wine and Baltic goods. Both served as customs collectors and also as collectors of the subsidy on wine, known as tunnage.12

Fifteenth-Century Decline

The decline of the town in the fifteenth century was to be as rapid as its rise had been in the twelfth and thirteenth. It had prospered and grown in these centuries because it had been ideally suited by its geographical position to benefit from the growth of international trade, and, above all, by the growth of the wool trade. During the fourteenth century it had continued to prosper, and even the Black Death could not halt the increase in its population for long. But we have seen that the nature and structure of the town’s economy changed considerably in the fourteenth century. Even before the Black Death, the fair had ceased to attract the number of foreign merchants who had attended in its heyday of the 1280s, and the quantities of wool shipped through Boston fell considerably during the fourteenth century, as did the quantities of wine imported. But Boston had continued to prosper, because its own merchants came to play a much greater role in both the wine and wool trades, and because the town’s commerce was boosted by the expansion of cloth exports, even though this was largely in the hands of Hanseatic merchants. It had also been helped by a healthy import trade in stockfish, Baltic timber and other ‘forest goods’, and, above all, dyestuffs and other products from the Low Countries, to meet the demands of the growing cloth industry, especially that of Coventry.

During the fifteenth century, however, the town’s overseas trade shrank dramatically. Almost since its foundation in the eleventh century, this had been the basis of its prosperity and subsequent growth, but from 1429 the quantities of wool exported from the port fell sharply. Cloth exports also diminished during the century, the town’s import trade fell away steadily, and by the end of the century the Hanseatic merchants, who had once played such a major role in the town’s prosperity, had almost all left and their buildings were described as dilapidated in 1481.

In the 1390s about 3,000 sacks of wool were still being shipped out of Boston every year and, at the beginning of the fifteenth century, this trade remained reasonably healthy. In the 1420s, about thirty wool merchants operated out of Boston and about 2,500 sacks were being exported annually. Boston had long slipped to third place behind London and Hull, and in 1424 only one Boston-based merchant was exporting more than a hundred sacks of wool, compared to five from Hull and fifteen from London. But Boston still handled about 20 per cent of the trade in the 1420s, just as it had a hundred years earlier. Exports slumped, however, in 1429, principally as a result of a trade embargo imposed by the Duke of Burgundy. Although there were periodic rallies, the level of exports from Boston continued to decline. By the end of the century they had shrunk by half, and the decline would continue well into the sixteenth century.13

This decline in the town’s wool trade might not have been so serious had cloth exports remained buoyant; unfortunately, this was not the case. The trade was very seriously disrupted by piracy and Anglo-Hanseatic maritime warfare in the 1460s, and never recovered. Whereas in the 1380s and 1390s English merchants were usually shipping at least between 500 and 800 cloths a year out of Boston (and in some years over 1,000) by the 1490s they were barely exporting fifty to eighty cloths each year. Hanseatic merchants were shipping about 2,500 cloths every year from the port in the 1390s, but their numbers were also in sharp decline in the last decades of the fifteenth century, and disappeared completely in the first years of the sixteenth century.14

While the exports of wool and cloth diminished, no other goods took their place. In 1490 the total value of all other exports shipped out by English merchants was reckoned at only £45. These were principally animal products, such as tallow, calf- and lamb-skins, butter and beef, a little grain and some vegetables, together with small quantities of lead and sea-coal.15

The town’s import trade also suffered a sad decline during the century, as fewer merchants – both native and foreign – chose to use the port. By the late fifteenth century many of the goods which had once arrived on the quayside in large quantities were now barely landed at all. Imports that in the fourteenth century had figured so frequently in the customs accounts, such as wine from Gascony, stockfish and oil – in which the Hanseatic merchants had particularly specialised – dyes, canvas and manufactured goods from the Low Countries, and timber, tar and iron from the Baltic, were now only occasionally seen at the port. In 1413 over £1,200 worth of goods had been imported at Boston by English merchants, but in the 1460s they were valued at less than a £100 a year. The number of ships to be found in the harbour by 1500 was but a fraction of those of earlier times. Wine imports would increase again in the early sixteenth century, but the decline suffered as a result of the disruption caused by the wars against France in the mid-fifteenth century, and the loss of Gascony, was never fully recovered. The quantities being imported in the 1490s were pitifully small, and even when they revived in the 1520s and 1530s, the quantities imported were at best only about a tenth of the tonnage regularly imported two hundred years earlier.16

Nor is there any evidence to suggest that the coastal trade increased to compensate for the loss of international trade. Indeed, what little evidence there is rather suggests the opposite. The small number of ships known to have been owned by Boston merchants in the sixteenth century certainly does not suggest a buoyant coastal trade, and the evidence of fees charged at the port by the Honour of Richmond for the use of the crane shows a similarly depressing picture of decline for all types of trade. In 1425–26 the cranage fees totalled £9 for the year; ten years later they were less than half this; by 1461–62 they had fallen to a mere £1, and at the end of the century the honour officials were collecting just 10s.17

As the port declined in importance, and the numbers of merchants living in the town decreased, so also did the population of the town. There are, unfortunately, no population figures available for the fifteenth century, but the decline in population in these years can hardly be doubted, for by the mid-sixteenth century we know that the population was only about half what it had been in the late fourteenth century. This impression is also confirmed by the fall in the rental income received annually by the Honour of Richmond from tenements in Boston. It approximately halved between 1434–35 and 1493–94.18

The rise in the town’s trade as an out-port for the Coventry cloth industry in the late fourteenth century prolonged the town’s prosperity long after the decline in the wool trade had set in, but in the fifteenth century Coventry itself was in decline and, to make matters worse, an increasing share of its cloth output was now exported through London, rather than Boston. Moreover, although Boston had been well placed geographically for the export of raw wool, it was not well placed for the export of English cloth. Most cloth in the fifteenth century was manufactured in the west of England, in East Anglia and in Yorkshire, and for all three areas there were other, more convenient ports through which the cloth could be shipped.

Boston’s fortunes were also closely linked to those of Lincoln, and that city’s decline was already apparent at the end of the fourteenth century. Its own cloth-making industry had collapsed at the beginning of the fourteenth century and its commerce was badly damaged by the silting up of the Foss Dyke, the ancient canal connecting the city to the River Trent. From as early as 1335, there were complaints that it was so obstructed that boats could not pass between Lincoln and Torksey. During the fifteenth century, Lincoln’s population and prosperity continued to decline. Between 1377 and 1524 its population shrank by about 40 per cent, and from being the ninth richest town in 1334, it had fallen to being the twenty-fourth richest by 1524. The worst effects of Lincoln’s decline for Boston, however, were for some years masked by the town’s fruitful link with Coventry.

All provincial ports suffered in the fifteenth century, to some extent from the increasing share of overseas trade which was being taken by London – especially Hanseatic trade – but few other ports suffered quite as severely as Boston. In the 1380s, 60 per cent of Hanseatic cloth exports from England were shipped through Boston, but by the end of the fifteenth century London accounted for 96 per cent of the trade and Boston for less than 1 per cent. Relations between Hanseatic and English merchants both in Boston and in other east-coast ports were often strained. English merchants strongly resented the privileges enjoyed by the Hansards in England, especially as their demands for reciprocal rights in the Baltic were unavailing, and the resulting conflicts and animosity may have encouraged the steady decline in the number of Hansards visiting ports such as Hull, Ipswich and Boston. One of the worst cases occurred at Boston in about 1470 when, according to Leland, ‘one Humphrey Littlebury, merchant of Boston, did kille one of the Esterlinges, whereupon rose much controversy’. Leland claims that this incident alone led the Hansards to leave the port, which was not the case as their numbers had long been falling and a few did continue to visit Boston after 1470. But such incidents could only speed the process, especially as in London they found much less hostility, as the Londoners were more concerned about the competition of the Italians.19

Boston was also becoming a less accessible port by the end of the fifteenth century, and therefore one that many sea captains would prefer to avoid. By 1500, the Haven was beginning to silt up as a consequence of a gradual rise in sea level. This was increasing the amount of silt available to block up the harbour while also reducing the gradient of the River Witham. Complaints about the state of the river and harbour would be frequently voiced for the next 200 years.

The Administration of the Town

Throughout the Middle Ages, Boston remained a seigniorial borough, administered by the appointees of distant lords and enjoying none of the self-government which we might expect to find in a town of its size and importance, and which was enjoyed by many far smaller towns. The only exception to this, we have seen, was the period shortly after the granting of the charter by King John in 1205, when, for just a few years, the townsmen enjoyed the right to elect their own bailiff. This taste of at least a degree of self-government lasted for not more than six years, and possibly less, for in 1211 the estates of the Honour of Richmond were back in the earl’s hands, and when a royal charter was granted in 1218, confirming long-established rights to hold a market and fair, it was given to the Earl of Richmond, not to the townspeople of Boston.

Until the town’s decline in the fifteenth century, it is not hard to see why the lords of Richmond and Tattershall, as well as the holders of the de Creoun fee, should have been keen to hold on to their rights in the town. For the Honour of Richmond in particular, the profits accruing every year in the late thirteenth century from the fair, the markets, the bridge tolls and urban rentals were considerable. In the fifteenth century, however, when the town was far less profitable, a grant of self-government would have been much less surprising. Two things, it would seem, prevented any change in the status quo. In the first place, the division of the town between three different lordships complicated the issue. No single lord could confer liberties and promote self-government without the agreement of the others.20

Secondly, it would seem that, for the most part, the leading citizens of the town – the merchants and local landowners – who might have been expected to dominate any corporation and serve as mayors and aldermen, were remarkably content to have manorial government. Among the less wealthy townsmen, it is likely that there would have been some discontent with the rule of the manor court, and its presiding official, the town bailiff. In 1347 a local revolt against the town’s lords did break out and the rebels elected their own mayor and issued their own proclamations, but it did not involve the leading townsmen, and the manorial officials were soon in authority again. Moreover, the revolt seems to have been as much to do with the high price of grain as with any specific discontent with manorial government. There were disturbances in a number of towns that year, constituting the first known wave of food riots in the history of the country. In Boston, ships laden with grain were boarded by the rebels.21

A number of reasons might be suggested to explain the apparent deference of rich merchants to non-resident aristocratic lords, which was so unlike the situation in a number of other towns under manorial jurisdictions. In Boston, there were some financial benefits to seigniorial jurisdiction. The responsibility for maintaining the common hall, the walls and the Barditch and other aspects of the fabric of the town, including the town bridges (which required very frequent repair) was taken by the manorial officials, and not directly by the townspeople. In a corporate town such tasks would be the responsibility of the burgesses and their corporation, and the expenditure would have to come from the burgesses’ ‘common purse’. In Boston, by contrast, the tasks of such maintenance were carried out by manorial officials using the lord’s income.22

Partly because of this, it would seem that in Boston there was a popular view – which was broadly true – that the townspeople and their lords shared a common interest in the town’s wellbeing and success. The town had been created by its lords; they had obtained its rights to hold markets and the annual fair, and had extended the length of the latter; and it was Alan de Creoun who, in the mid-twelfth century, had constructed the sluice to scour the River Witham and thus ensure that Boston became the main out-port for Lincoln. As tenants of the Earls of Richmond, the townspeople could enjoy the liberties of the Honour of Richmond, including exemption from tolls throughout England, and they could expect the earls to enforce this right on their behalf whenever and wherever it might be challenged. Also, although the townsmen lacked the self-government and corporate identity of a borough, such as was enjoyed by the townsmen of Grimsby, Stamford, Grantham and Lincoln, they had nevertheless always possessed most of the privileges of urban life: free tenure and fixed money-rents, the right to buy and sell land, and control of their own time.

The key factor, however, in ensuring that the town’s merchant elite remained co-operative and content with manorial rule was probably that many of them enjoyed recruitment into it. One of the greater merchants who, we have seen, served the Honour of Richmond as a bailiff for the town was John Belle. He and another Boston merchant, William Spaigne, were both promoted to high office in the Honour. Spaigne served as feoder for the Honour’s estates in both Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire, and then as steward for all its land holdings. Another who is known to have served as bailiff (from 1375–1379) was the Boston merchant, Philip Gernoun, who was, like Belle, also an alderman of the Guild of Corpus Christi, a wealthy landowner, and one of the town’s eleven oath-takers of 1388. Another was John Clerk, who was a Boston wine importer, a buyer of cloth in the 1380s and 1390s, a Boston landowner and, with his wife, also a member of the Corpus Christi Guild. He was appointed bailiff for the town in 1384.23

By no means were all the bailiffs merchants of the town, but many, it would seem, were, and there were certainly many unofficial links and ties of friendship which must also have helped ensure co-operative relations. One of the most important was common membership of the town’s major guilds, and particularly the Guilds of St Mary and Corpus Christi. The lords of the town themselves entered the Corpus Christi Guild as ‘brothers and sisters’ of the leading townsmen. One of the town’s lords, Humphrey Bourchier, the holder of the Tattershall fee in the 1460s, even became the alderman of the guild in 1466.24

The guilds also acted as clubs for the leading figures of the town and could act as a forum for the expression of their views and an outlet for corporate organisation. Following the establishment of the Boston staple in 1369, this also acted as an assembly of merchants, which elected its own mayors and constables. Walter Pescod became constable of the staple in 1390. We have also seen that the richest and most powerful Boston merchants – men such as Frederick Tilney, William Spaigne and John Belle – also enjoyed considerable administrative responsibilities, which were much greater than those enjoyed by the leading men of less prosperous towns, whether or not they were self-governing boroughs. Boston’s merchants might be appointed as collectors of royal customs and subsidies at the port, and they could also hold royal commissions giving them power to hold special regional courts of law, commissions of array (to raise royal forces) and to raise taxes.

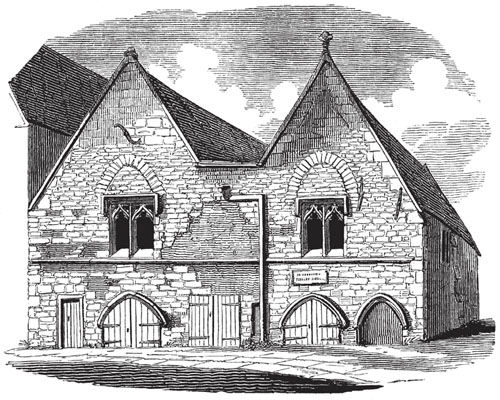

Gysor’s Hall, named after an early tenant, John de Gysor, a London merchant who was twice Mayor of London. It was used as the Honour of Richmond’s manor house from the late fourteenth century.

The headquarters of the manor, the ancient manor house that stood facing the Mart Yard, was said to be in a sad state of disrepair by the 1330s, but seems to have continued in use until the 1370s, when John of Gaunt ordered that another property of the Honour, a house known as Gysor’s Hall, should be used instead. This had been built in the first half of the thirteenth century and took its name from a London wool merchant who had been one of its early tenants. It was a little more central than the old manor house, standing a little further to the north, in South Square. It was demolished in 1810, and its stones reused to build the ground floor of a warehouse, that still stands today, although the building has now been converted into apartments.25

The Guilds and the Religious Life of the Town

The fourteenth century witnessed a considerable increase in the number of religious guilds established in the town. This was in part a sign of renewed religious enthusiasm, particularly following the devastating loss of life brought by the Black Death in 1349, but it was also another indication of the considerable prosperity of many of the town’s inhabitants in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. At the beginning of the fourteenth century there existed only one guild, that of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which had been established by the town’s leading merchants in 1260, and would remain the wealthiest guild in Boston until the dissolution of the guilds at the time of the Reformation. A second guild was not established until 1335, when the Guild of Corpus Christi was founded, but by 1389, when an inquiry into the number and wealth of the country’s guilds was conducted by the government of Richard II, there existed at least three more major religious guilds: those of St Peter and St Paul, St George and the Holy Trinity, and five more minor, unincorporated guilds (those of the Ascension, St James, St John the Baptist, St Katherine and Saints Simon and Jude). Further minor guilds were established in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries: the Holy Rood, All Hallows, the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Apostles, St Anthony, St Thomas, the Seven Martyrs, the Fellowship of Heaven and St Anne. By the 1520s there were at least nineteen guilds in the town.26

The certificates issued to the guilds in 1389 identify their founders. The Guild of St Peter and St Paul – like the earlier Guilds of St Mary and Corpus Christi – was founded by Boston merchants, but the Guild of Saints Simon and Jude was founded by ‘mariners of Boston’, Holy Trinity by the local bakers, and St John the Baptist by the leatherworkers. These were not, however, craft guilds. Their aims were primarily religious: the salvation of their members’ souls, the souls of former members, their benefactors, as well as ‘all Christian souls’. The wealthier, incorporated guilds could afford to maintain their own chaplains to perform the last rites, to pray for living members, and to maintain a constant cycle of prayers for the souls of deceased members. The lesser guilds could not all afford this but maintained their own altar in the church and paid for candles, vestments and services, and some also took responsibility for meeting the needs of pilgrims visiting the church. The Guild of St Anne, for instance, seems to have been formed by a small Benedictine nunnery established in the town to provide accommodation for pilgrims visiting the reliquary believed to house the finger of St Anne, which had been given to the Guild of St Mary and was kept in the church. The nunnery may have stood in Wormgate, or possibly close to the site of St Anne’s Cross, where St Anne’s Lane can still be found, at the southern end of High Street.27

The seal of the Guild of St Peter and St Paul.

The five major incorporated guilds of the fifteenth century – St Mary’s, Corpus Christi, St Peter and St Paul, Holy Trinity and St George – all had their own guildhalls. The building still known as the Guildhall, on South Street, was St Mary’s guildhall, built in about 1390 and one of the earliest brick buildings in the county. The Holy Trinity guildhall probably stood on Gascoyne Row in Wormgate, for it was here that it surrendered its properties to the new corporation in 1545, and the St Peter and St Paul guildhall was most likely situated at the northern end of Wide Bargate. Excavations under Poultry Yard, next door to the New England Hotel, have revealed late medieval brickwork, fifteenth-century pottery, and a coin from the same period. Moreover, the guild’s name is still commemorated in the area by the street name, St Peter’s Lane, and the former name of the hotel was the Cross Keys, the traditional symbol of St Peter. The Guild of St George was probably the last to erect its own hall, and, appropriately, it was the furthest from the church, on the far side of the river, between St George’s Lane and Pinfold Lane. It was demolished in 1896. The location of the Corpus Christi guildhall is less certain. Until recent times it was assumed to have stood in the vicinity of Corpus Christi Lane, off Wide Bargate, but a strong case has now been made for identifying the much altered Shodfriars Hall, on the corner of South Street and Sibsey Lane, as the Corpus Christi guildhall.28

St Mary’s Guildhall is probably built on the site of an earlier hall. Stretching back 150ft from its frontage on South Street, it was built to accommodate the very large membership of the guild when they met together upstairs, in the banqueting hall, for the annual patronal dinner. Pevsner and Harris describe it as ‘a poignant reminder of Boston’s medieval prosperity’. Before the dinner began, a new alderman, chamberlain and other officers would be appointed for the coming year, and this occasion, together with the dinner also held here during the feast of Corpus Christi, would be one of the high points of the Boston social calendar in the mid-fifteenth century. An inventory dating from 1533 tells us that the members sat down to fourteen long trestle tables, some of which were so long that they required tablecloths between 8 and 10 yards in length. Above them were five candelabras and the banquets were served on pewter and latten plates and dishes, prepared nearby in the well-equipped ‘over-kitchen’. Today the banqueting hall has Georgian panelling, but five bays of the medieval roof can still be seen above ‘with crown-posts resting on tie-beams whose braces spring from grotesque corbels’, to quote Pevsner’s and Harris’ description.29

The Shodfriars Hall dates from between 1350 and 1375, and it is the largest timber-framed building surviving in the town. It was, however, heavily restored and much altered in the 1870s, so that its original appearance can only be seen now in nineteenth-century engravings. Its recent identification as the Corpus Christi guildhall stems partly from similarities noted by Pevsner and Harris between the original building and the famous guildhall of similar date at Thaxted in Essex. Another clue, however, comes from the description of the guildhall given in a late fifteenth-century rental. This described the ‘principal mansion’ of the guild as containing a hall, parlour, a kitchen and two chambers, and located it close to the river, with its own staithe ‘aganeth the frontage’. The guildhall, the rental says, was called the ‘Goldenhows’. There is no local tradition, however, linking the Shodfriars Hall with the guild, and the link must remain for the moment a matter of speculation. It may instead have been the house of a wealthy fifteenth-century merchant family. The name ‘shodfriars’ refers to the Dominican friars, who occupied much of the area between the building and St Mary’s Guildhall.30

St Mary’s Guildhall in the mid-nineteenth century. (Drawn by G.F. Sargent.)

The five incorporated guilds all possessed considerable assets at the time of the Reformation, and their lands alone were valued at over £520. These were mainly in and around Boston, but St Mary’s – whose land holdings were the most extensive – acquired properties also outside Lincolnshire, including an estate in Calais. A surviving account book of the guild’s officials from 1525–26 reveals that at this time the guild employed two bailiffs to collect the guild’s rentals and manage its properties in the Boston area, while two other officials were responsible for supervising the repair of houses, sewers, gutters and sea dykes. Four vicegerents were also employed with responsibility for collecting the guild’s income from the rest of the country, each given a wide geographical area, and they – like the bailiffs – were responsible to two chamberlains, who, like the alderman, were not paid but held their position as an honour and public duty.

As well as the substantial income from property rentals, the guilds could also raise money from entrance fees and annual subscriptions. The account book of 1525–26 shows that the two chamberlains of St Mary’s guild spent much of their time riding about the country with their servants and clerks collecting the annual payments and recruiting new members, assisted in different parts of the country by one or other of the guild’s vicegerents.

Further – and very substantial – income also came from the gifts made by pilgrims to the guild chapels visiting the holy relics and from the sale of papal pardons, known as indulgences. The latter were particularly important for St Mary’s Guild. From 1401 the guild was able to use the promise of an indulgence as a major inducement to the people of Boston to seek admission to the guild and pay the admission charge of 6s 8d, plus the annual subscription of 1s, whether they could really afford it or not. In 1401, Pope Boniface announced that from that date, 100 days’ remission from penance was promised to all guild members who were present whenever Mass was celebrated with music in St Mary’s guild chapel. In 1451 the guild managed to persuade the Pope, Nicholas V, to extend the scope of the indulgences offered, and these were constantly renewed and extended further during the rest of the century. St Mary’s also gradually accumulated an extensive and unique relic collection which attracted fee-paying pilgrims. It was housed in its large and beautifully decorated chapel in the south-east corner of St Botolph’s. As well as the finger of St Anne, set in silver and gold, pilgrims could also see a bone of St Christine, also set in gold and silver, the bones of the Holy Innocents, part of the stone of Calvary, part of the stone on which Jesus stood when he ascended into Heaven, a piece of the Holy Sepulchre, and some of the milk of the Virgin Mary, contained in a silver and gilt case. Pilgrims could also view the shirt of St Patrick in the nearby Corpus Christi guild chapel.

A medieval building on South Street, in about 1850; possibly the Corpus Christi guildhall and now known as Shodfriars Hall.

Shodfriars Hall today.

Many townspeople belonged to a number of guilds, but only the wealthy could afford to join the Guild of Corpus Christi. Founded in 1335 by particularly rich local merchant Gilbert Alilaunde and twenty-nine other well-to-do merchants, it maintained its position throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries as a rich man’s club. The admission fee of £2 4s 4d was far higher than that of any other guild. Membership was a statement of wealth and success, and it would seem from its surviving register of members that virtually every well-to-do Boston merchant of the time (and also often their wives) wished to join, as well as other members of the social elite, and particularly the clergy. When, in 1349, it sought formal incorporation from the Crown, it admitted not only King Edward III and Queen Philippa to membership, but also their eldest son and three prominent members of the royal household. The register shows that admissions fell sharply following the Black Death, which struck that year, but began to recover in the 1370s and reached a peak in the 1390s, the last years of Boston’s ‘golden age’ as an international port. In the fifteenth century, not surprisingly, the proportion of merchants joining the guild declined but, owing partly to increasing numbers of clergy seeking admission, the total number of admissions was rising again from the 1430s and remained remarkably stable until a sharp fall in the 1490s.31

For many of Boston’s inhabitants the guilds must have provided the chief focus for both their religious and social lives. The conviviality of the patronal feasts helped create a sense of unity and belonging, and brought some entertainment to the winter months. St George’s met on 23 April, Saints Simon and Jude on 28 October and St Katherine on 25 November. In late May or June the principal event was the Corpus Christi procession, when the entire town flocked to the streets to witness the Host being carried in solemn procession. All the town’s guilds would take part, each led by their aldermen and chamberlains, with the two most senior – Corpus Christi Guild itself and St Mary’s – bringing up the rear. The procession would be led by the numerous clergy of the town, including the many guild chantry priests, together with the town’s most important officials, including the bailiff, his deputies and the mayor of the staple. Banners, crosses, torches and thuribles were carried by members of the guilds and musicians were also sometimes employed. Plays depicting scenes from the Bible were also performed, as at Lincoln and in many other towns. There are references to a ‘master’ or ‘searcher’ of plays in the accounts of the Guild of St Mary, and in 1518 the guild paid for the building of a Noah’s Ark to be carried in the procession by a team of eight men. According to the nineteenth-century Boston historian Pishey Thompson, the Corpus Christi plays were performed at the Franciscan friary. It was the friars, presumably working closely with the guilds, who co-ordinated the preparations for the performances.

The guilds were at the heart of the work and worship of the church. St Mary’s Guild was closely involved in the initial work of planning and building the new St Botolph’s, and the five major guilds all made it the highest priority to build their own chapels in the church. St Mary’s chapel occupied the eastern end of the south side of the church, and in about 1389 the Guild of St Peter and St Paul began to build their chapel across the aisle from St Mary’s, at the east end of the north side of the church. The Guild of Corpus Christi had its chapel built to the east of the church porch, and it was probably completed between 1349 and 1354, next to three bays of the south aisle. It was said to have been demolished in the seventeenth century, but the blocked-up doorways that once linked it to the south aisle are still clearly visible. The Holy Trinity Guild chapel probably stood in the north-west corner of the church, and the present Cotton Chapel was probably the location for St George’s chapel. The smaller guilds had their own altars along the walls of the church, and paid for candles to be lit in front of images of their patronal saint. At Easter all the altars of the church would be lit by candles, and a grand procession through the church to the chancel included the aldermen of all the guilds, dressed in rich robes and preceded by the guild chaplains, wearing the livery of their guilds, and the parish clergy. Saints’ days were also often the days chosen for the annual commemorative services (or obits) held in the church for those former members of the guilds who had asked for such services in their wills, and who had left sufficient money or property to the guild to pay for them. All such services were announced the day before by the parish bellman walking through the town. When the merchant Frederick Tilney, who was one of the town’s richest men, made arrangements for his anniversary, he asked that no less than forty chaplains should always attend his service. The church choir enjoyed a high reputation at the beginning of the sixteenth century and this also owed much to the support of the guilds, and especially St Mary’s, which paid the salary not only of the choirmaster but also that of the warden of the choristers, one of whose responsibilities was to ensure the boys said their matins each day. The housekeeper employed at the guildhall was also paid an extra allowance for washing and mending the choir’s robes.32

As part of their religious purposes, the guilds were also much involved in works of charity and the provision of education. From the time of its foundation in 1260, the distribution of bread and fish to the town’s poor was an important commitment of St Mary’s Guild, and by the fourteenth century it had established a ‘bedehouse’ for twelve poor people, to which the other guilds would also later subscribe. When the Guild of Corpus Christi received its licence in 1349 it committed itself to paying 2s a week to ‘those in poverty’. Also, the instructions for members’ obits usually ended with a request for money to be distributed among the town’s poor.

When the town’s grammar school was founded, probably in the first half of the fourteenth century, St Mary’s Guild was the chief benefactor, ensuring the payment of a schoolmaster. But other guilds, and in particular those of St Peter and St Paul and Corpus Christi, appear to have also contributed to maintaining it. Very little is known about the medieval school but at the time of the Reformation it was located in Wormgate, and the schoolhouse was then owned by the Guild of St Peter and St Paul. It was founded as a song school, and it is likely that it was modelled on the song school that had been long established at Lincoln. At first it probably took just a few boys aged about 7 to 10 and taught them the alphabet and reading, basic prayers, and the singing of plainsong, whereby they would also be introduced to the study of Latin. It may also have taught writing. As slightly older boys came to be taught as well, and the school became a grammar school, their education would focus mainly on acquiring the skills of reading, writing and speaking Latin, a useful preparation not only for a career in the church, but also in business and the law.33

The Hussey Tower and Other Medieval Buildings

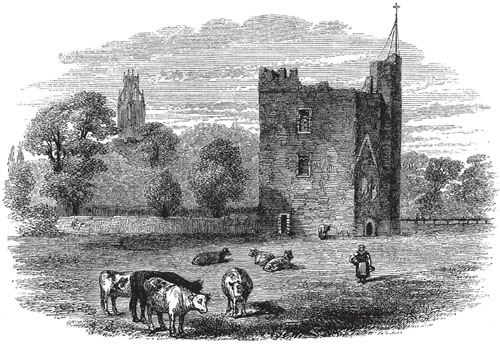

The former guildhalls of St Mary’s and (probably) Corpus Christi guilds, together with the Dominican refectory (now Blackfriars Arts Centre) are among the most important medieval buildings surviving in Boston today, but they are not quite the only survivals from this period. Another is the Hussey Tower, built about 1450 and still standing at the southern end of the town. This is the only survival from a substantial manor house which was built for a prominent and very wealthy Boston man, Richard Benyngton, who served as collector of customs and subsidies for the town in the 1430s, and as a Justice of the Peace between (roughly) 1430 and 1460. The house was probably inspired by the slightly earlier Tattershall Castle, built by Benyngton’s friend and fellow JP, Ralph, Lord Cromwell and, like Tattershall Castle, it was built of brick manufactured in the Boston area. The original house, which was attached to the tower, was two storeys high and had a gatehouse on South End, a brewhouse, mill house and stables.34

Back in the town centre it is possible to still find a few examples of at least fragments of late fourteenth and fifteenth-century timber-framed houses. At Nos 25 and 35 High Street are the remains of two medieval timber-framed open halls, both built at right angles to the street, with two-storey shops at the front facing the street. On Mitre Lane, back on the east side of the town, there is Pescod Hall, a timber-framed building with brick infilling. This was a fifteenth-century merchant’s house and originally had a hall attached to the west wall. It was taken down and rebuilt in 1972, and stands now at the centre of the Pescod Square shopping development. Sadly, however, this is almost all there is. Most of the medieval street pattern, however, does still survive. It was largely spared when the route was chosen for a new inner ring road, the John Adams Way. Unfortunately, though, the new road did destroy much Georgian property.35

Hussey Tower, around 1850. Named after its Tudor owner, Lord Hussey, whose properties were seized by the Crown in 1536, when he was arrested and executed following his failure to suppress the Lincolnshire Rising and his subsequent support for the Pilgrimage of Grace in Yorkshire. It was later granted to the Boston Corporation. In 1564, however, it was still known as ‘Benyngton’s Tower’, after its original owner. The house attached to the tower was demolished in 1725.

Hussey Tower today.

Pescod Hall today.